The champ sits astride his cutdown speedster with the confident look of a winner. Mud chaps cover his pants and the thin tie complements his white shirt. A blazer is flopped on the seat next to him as if he is going to some event. The name “Blitzen Bean” given to the speedster no doubt parodies the famous “Blitzen Benz” racer of that period, which ferried many a racer to glory on sandy beaches and race tracks. This lucky fella, however, made his own mark in the Klondike, the White Horse to Dawson elapsed time run, in 1913.

Whitehorse to Dawson City, also known as The Overland Trail, was an important route for miners of the period, but it was exclusively a horse-drawn trail until 1912. The Dawson Daily News on May 5, 1920, reported a tale from retired stage driver (also known as a “skinner”) “Simmy” Feindel that he set an elapsed time record for the 530-kilometer trail (330 miles) in 1901 while driving some “Klondike Kings” to Dawson. It took Simmy three days and nine hours. In 1912 a couple drove a Flanders 20 in mid-December to be the first to drive the trail in a car during winter, but they broke down.Winter driving on a crude dirt road, 40 below zero on a good day… now, is that crazy, or what?

However wacky that reads, mining people had to move for their work, and later that month the Yukon Gold Company sent two of its staff, Commissioner George Black and C.A. Thomas on a trip from Whitehorse to Dawson. George Potter drove them in Thomas’ Locomobile and reached Dawson in 35.5 hours.

I wonder what our young driver achieved in 1913 driving the Blitzen Bean?

The gold dredge in the background of the photo is similar to the ones that Tony Beets uses to mine gold as seen on the Discovery Channel’s hit program, “Gold Rush.” Although not visible in this photo, the gold dredge floats in its own pond as it processes placer gold (loose flakes in sediment), with the pond used as a source of water to process the paydirt. The buckets on a track (on the right) scoop up paydirt from the sides of the pond, dump it on a wash bed inside the dredge, and the washed gravel-dirt slurry is guided through a sluice box where the gold precipitates out. The waste remainder is conveyed out behind the dredge (on the left) via a tailings stacker, which deposits the tailings in piles. If you look carefully at the stacker in the photo, you can see tailings being deposited out of the back. More information on dredges can be found on YouTube; here’s an example of a dredge video: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ad_nkRHTKdc

The speedster in the foreground of that photo above is allegedly a 1910-1911 Flanders Model 20 that had been stripped of its body, fenders, and accessories to make it into a cutdown competition car; you can see the headlight brackets that were left on the frame.

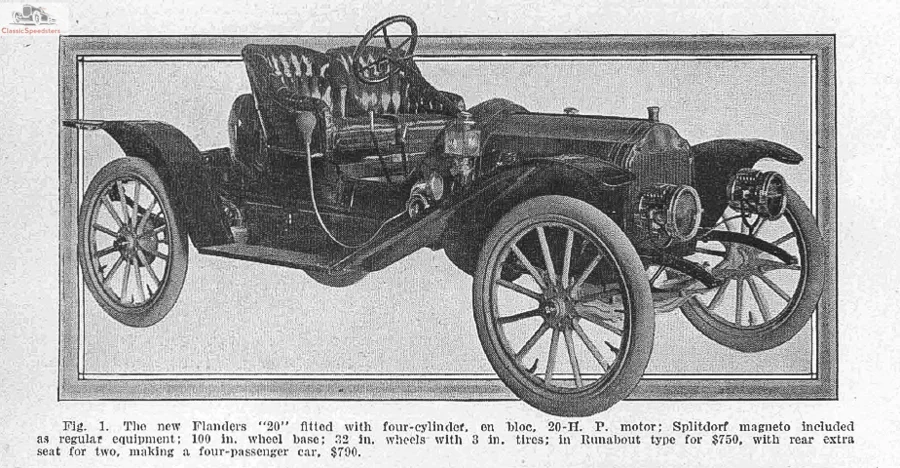

1910 Flanders 20 Roadster. Image courtesy Horseless Carriage Foundation Inc.

The Flanders 20, which was conceived by Walter Flanders and designed by his engineer James Heaslett, was manufactured by the E-M-F Company from 1910-1912. Flanders was a production line expert and machine salesman who had honed his skills working for Henry Ford before going on to work at a start-up called Wayne Automobile Company in 1906. Flanders partnered with Barney Everitt and Bill Metzger to form E-M-F in 1908, which dominated auto production for the next several years. Not without controversy, as auto production in the first few decades of the twentieth century were wild times. But that’s a story for another post…

The Flanders Model 20 came in three basic body styles: a utility runabout, a suburban tourer, and a racy roadster. The Model 20 was built on a 100-inch wheelbase, weighed about 1200 lbs, and was priced at $750 to compete directly with Ford’s Model T. Its four-cylinder engine, radiator, steering mechanism, and dash were all carried on a unique subframe; work on any one piece was made easier by unbolting the subframe and lifting the whole unit out for repair. The Flanders 20 also had an improved three-speed transmission for 1911, dual ignition that used a Splitdorf magneto and battery, internal expanding brakes, and other up-to-date technology that would make it appealing to both the everyday owner as well as erstwhile tinkerers who wanted to make a dependable and inexpensive cutdown.

1910 Flanders 20 model types

E-M-F did produce a speedster model, one known as the Witt Special, for 1911-12, but it is more likely that the Blitzen Bean may have been a 1912 Flanders 20 Speedster, the latter being a limited production stripped version of the Racy Roadster. When compared to factory photos of the roadsters offered for 1910 through 1912, the Blitzen Bean is different in that it has a lowered, raked seat, and its gas tank appears to be circular in section like what the Speedster model had. However, the transition from engine cowl to passenger compartment seems a little unfinished in the Bean, calling into question what year model this speedster actually was, and whether it was factory or home-built.

1912 Studebaker-Flanders 20 Speedster. Image courtesy http://EMFAuto.org

Even if the Blitzen Bean had been converted from a Racy Roadster, the roadster’s initial low cost provided a good platform with which to easily make a street or competition speedster. The two-speed transmission, which was later improved to a three-speed, was carried at the rear for better weight balance. Semi-elliptical springs in the front and full-elliptical in the rear made a well-handling car for the period. The 155 cubic inch engine had two sets of twin-cylinder blocks, with drop-forged con rods and camshaft, a flat crank, and other items that made it a solid engine that would easily be hopped up with a little effort. These robust features provided an opportunity for the back-yard tinkerer to make a sporty and reliable speedster.

The Blitzen Bean was no doubt a hot machine!

Many thanks to Chris Bamford, who volunteered this photo. For more history regarding this interesting and challenging part of the world, check out the Dawson City Museum at http://www.dawsonmuseum.ca.

Next post: more about E-M-F history, and a Flanders Model 20 Speedster goes to auction…