From Coal to Diamonds

Reliance Automobile Manufacturing Company was organized in 1903 and its biggest contribution to the auto industry turned out to be the invention of the side-entrance tonneau touring model. Reorganized in 1904, Fred O. Paige was brought in to manage the company, and under his watch the company sold off its car line, and then sold its truck business to General Motors in 1909. With nothing left to sell, Paige would leave soon after to begin his own car company.

Harry Jewitt portrait c. 1905. image courtesy Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library

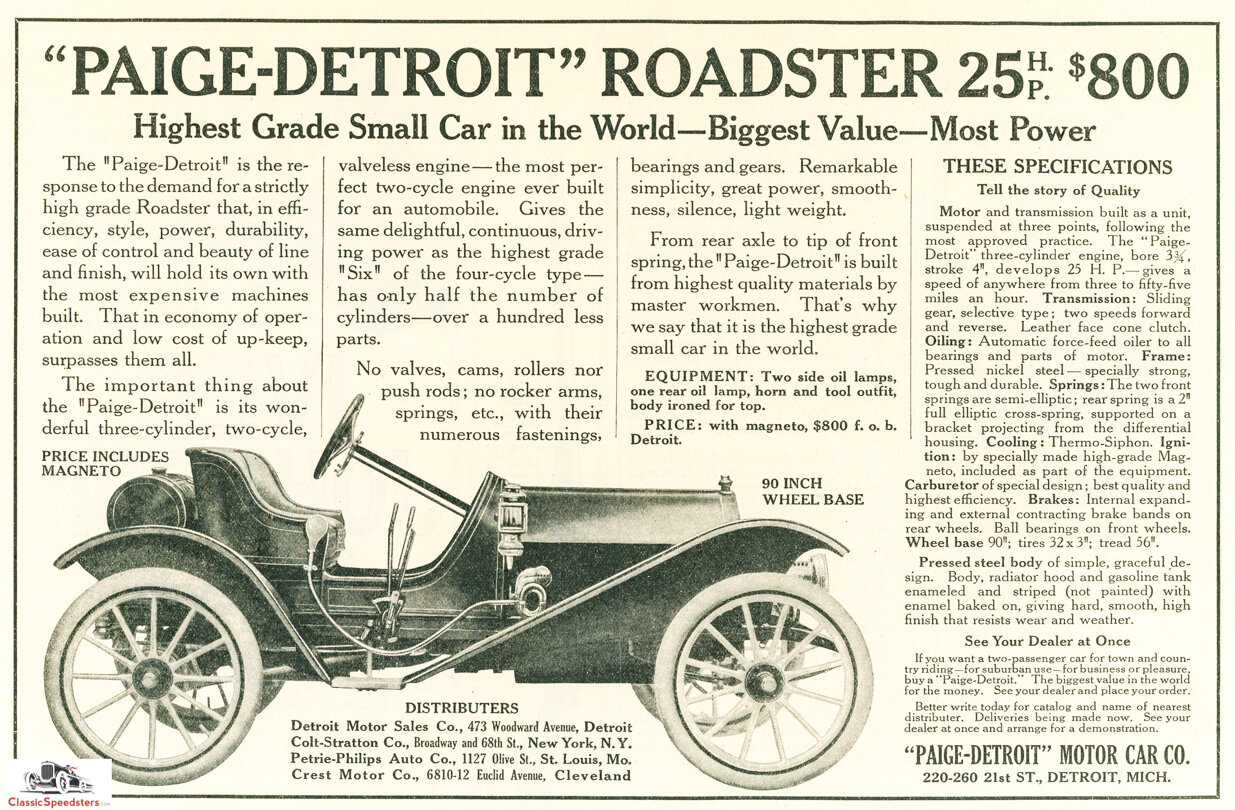

Meanwhile, Harry M. Jewitt had been making his fortune shipping West Virginia coal to Michigan. In 1909 Jewett got a ride in Paige’s new car and was sold on the idea to back Paige’s promotion of a two-cycle, three cylinder runabout that was built on a diminutive 90 inch wheelbase. Jewett and his team organized the Paige-Detroit Motor Car Company around this car in 1909, capitalized the company with $100,000, and installed Fred O. Paige as its president. They were off to the races!

1910 Paige-Detroit with a two-cycle engine on a 90” wheelbase. ad courtesy AACA Library

1910 Paige-Detroit chassis. Note the three cylinder two-cycle engine. catalog image courtesy AACA Library

Paige-Detroit

Problems with those initial and somewhat impulsive decisions soon became clear to Jewett: factory operations were not up to par, the president did not display the needed leadership, and – well - the car was basically no good. So, in late 1910 Jewitt cleaned house, reorganized the whole shebang, and began transitioning the company to using a four-cycle, four cylinder engine as the car’s power plant and in a larger wheelbase.

1911 Paige-Detroit ad touting new four-cycle engine. ad courtesy AACA Library

Jewett continued the name “Paige-Detroit Motor Car Company” in company materials, but eventually it would be interchanged with the “Paige Motor Car Company”, depending on the application. And the cars would now be known as “Paiges.” Go figure…

Paige, but also, Paige-Detroit

By 1912 the Company was using both names in its literature, ads, and operating title, a practice that they would continue into the 1920s. However, 1912 signaled a renewal of the company from start-up to a fully operational independent manufacturer.

1912 Paige-Detroit catalog. brochure image courtesy AACA Library

To mark this change as well as up its game. Jewett added jazzy descriptors to model names. In this context, Paige’s first speedster emerged – the Brooklands – and boy, was it snazzy!

1912 Brooklands, all the money in 1912! brochure image courtesy AACA Library

Like all 1912 Paiges, the Brooklands ran on a 104 inch wheelbase with a 56 inch track, other models using a 60 inch track. The frame was channel steel and the wooden artillery wheels had demountable rims with 32 x 3.5 inch tires.

This ad for 1912 shows the available models of Paiges. ad image courtesy AACA Library

The four-cylinder engine had a bore - stroke ratio of 3.5 X 4 inches, giving it a 154 cubic inch displacement and a 25 horsepower rating. One feature worth noting was accessibility to the crankcase via side plates, something worthwhile if you had to reline the bearings and didn’t want to remove the whole engine to do that.

Company brochure showing 25 Hp engine and related parts. brochure image courtesy AACA Library

The Brooklands itself was equipped with a Disco self-starter, tools, and five lamps as well as a Prest-O-Lite tank. This was quite a package for all of $975 FOB!

For 1913, 1914, and in 1915, Jewett had the good sense to offer a racy model, alternately calling them a “Speedster” or “Speedway Raceabout” to signify their sporty nature. Unfortunately, a lack of documentation and photos doesn’t allow any discussion of details, but no doubt they were well-built, as Paiges carried that reputation and were well-known for being rugged and classy.

One photo of a 1913 Paige Speedster was posted on an AACA club forum site, which indicates that the Paige of this era presented in conventional cut-down style. A pity that we don’t have more to share!

1913 Paige Model 25 or 36 Speedster. image courtesy AACA Speedster Forum

The Paige Daytona Speedster

Paige became a successful independent during the pre-WWI years of 1916-1918 but did not offer a speedster model for sale. However, in 1919, and maybe as a promotional tool to revive its somnambulant auto sales, Paige produced a prototype six cylinder speedster in 1919 for its upcoming series 6-66 line. The car itself was raced on the beach at Daytona and caused quite a stir by employing “Smiling Ralph” Mulford as pilot. As seen in the ad, a passel of stock car records fell, enough to allow Paige bragging rights as “the stock car champion of the World!”

1921 Paige on Daytona Beach, Ralph Mulford piloting. ad courtesy Bill Roberts collection

The Paige Daytona represented the high point of Paige’s speedsterism. Produced for three seasons as a 6-66 or 6-70, Paiges used Continental 331 CID engines that produced from 66-70 horsepower and were reworked by staff for even closer tolerances and smoother performance than what Continental typically offered.

The Daytona Speedster in two-passenger form and the Daytona Roadster with a retracting “mother-in-law” seat followed conventions set by other speedster models of the era that had evolved to the semi-enclosed sport body. Style-wise, it would take some scrutinizing to differentiate the Paige from the Marmon Model 32 Speedster, the Kissel Gold Bug Speedster, and others who competed in this arena.

1923 Paige Daytona, factory image. courtesy Bill Roberts collection

Nevertheless, Paige wanted notoriety, and with this record-setting speedster they would gain some clout and improve their sales during the early to mid-twenties. After all, a speedster in the showroom always brought folks in the door! Paige Postwar sales numbers were a handsome 15,700-plus in 1919, with an understandable dip to under 9,000 during the 1921-22 depression, as all companies were experiencing similar sales corrections.

But, by the time that the Daytonas had blown through and departed on down the road into history, Paige had rocketed its sold models to over 43,000 in 1923. Thank you, speedsters!

Mid-twenties doldrums pushed Paige sales down to 37,000 by 1926, and although this was considered a normal cyclical correction of 15%, it was too much for Jewett, who had heavily leveraged the company. He was now on the losing side of the black-red line. It was time to rethink.

Paige, Graham-Paige, Then Graham

One more push was given to boost the company’s fortunes with a new model line and attendant publicity in 1927. Advertising for the Paige and lower-cost Jewett models came out swinging with the slogan “A New Day,” promoting a woman’s right to own and drive her car, as well as sharing it with her daughter. Without the husband around. Fancy that!

1927 Paige 6-45 coupe ad. Note the target audience! ad courtesy Bill Roberts collection

Also insinuated into the margin of this ad were company statistics to quietly remind owners, past and (hopefully) future, that the company was on solid ground and had a great future:

Assets of $20,000,000

Worldwide Dealer Organization

Never Reorganized – Never Refinanced

etc. etc…

All this while Jewett was looking for a buyer, as Paige sales were tanking with no letup in sight. Jewett had had enough.

The Graham brothers, glass bottle magnates who had also created a very successful truck body company that they subsequently sold to Dodge in 1925, were eager to get started with the auto trade. Seeing an opportunity with a down-on-its-luck storied brand, they stepped up and bought the company in June of 1927 for $4 million in cash and $4 million in promised improvements..

Using up unused parts and rolling stock in the Paige factory, the Grahams would reorganize as Graham-Paige Motors Corporation, infuse the company with needed cash, and produce the 1928 Graham-Paige. They introduced the 1928 Graham-Paige at the January New York Auto Show to much acclaim and sold the cars with great fanfare at the crest of the Roaring Twenties market.

After an explosion in sales of over 73,000 cars for 1928, the Graham brothers would begin the transition to making their own automobile, the Graham, by the 1931 season. With model expansion and more purchased factory space, the Grahams planned for more success, only to meet the headwinds of the Great Depression in 1932. Their best year for sales was their second, 1929, and those two winning seasons allowed the company enough capital to slog through the Threadbare Thirties with continually-dwindling sales until the onset of World War II closed the book on Graham automobiles.

But Wait…

There’s more to this story, such as Graham-Paige’s failed partnership with Hupp, then Reo, the intrusion of Kaiser-Frazer Corporation, Graham’s pullout and then purchase of Madison Square Garden, and now its ownership of the New York Knicks and other sports teams. So not everything went sour on that lowly Paige-Detroit auto company, which turned out to have more lives than a cat!

But speedsters are no longer involved, so we’ll happily close our story here…

1919 Paige Daytona Speedster prototype at the 2011 Amelia Island Concours. editor photo collection

Our automotive libraries serve as necessary resources for historians and the general public, and their services help maintain journals such as this one. If you know of someone who might have a collection of automotive history literature or images, please encourage them to donate what they are no longer using.

Thanks also for images shared by Bill Roberts at wcroberts.org. Roberts has maintained a Paige-Detroit history and registry that helped make this post possible.

If you haven’t yet subscribed to this blog, a red box is provided for you to do so at the right (or up), depending on your device. We use a two-step signup process to protect your security.

If you’d like to share this post with your friends, please click on the social button at the left (or down).