So 19th Century

Just the name “Locomobile” sounds like steam engines, ironworks, and 19th century industrialism, and the two men who formed the company had feet in that century.

John B. Walker. image courtesy Wikipedia

John B. Walker, a property developer and entrepreneur who had purchased Cosmopolitan magazine in 1899 as a turn-around opportunity (which he did), was itching to do something with that new phenomenon—automobiles. He took an interest in the work of the Stanley brothers, made them an offer to buy the company, and kept pestering them until they accepted. Then Walker turned around and offered half interest in his steam car business to his neighbor, Amzi L. Barber, only Walker charged Barber what Walker had intended to pay the Stanleys. So Walker got his half of the business for free! Ah, well—that’s business….

Amzi L. Barber. image courtesy Wikipedia

At that time, Barber was known as “the asphalt king,” as he had founded a paving company with his brother-in-law, secured exclusive rights to the largest natural source of asphalt called Pitch Lake in Trinidad, and then went on to pave most of Westchester County in New York. By 1900 Barber’s company had laid over 12 million square yards of asphalt in 70 American cities, but Barber wanted out, as the company had been turned over to a trust. A car company seemed like the perfect exit plan.

These two 19th century industrialists had no clue how to run a car company, but they had hired the Stanleys to stay on a year, long enough for the two principals to split up over a disagreement. Barber took over Locomobile and moved it to Bridgeport, while Walker started another car company, failed, then went back to Cosmo until he sold it in 1905 to William Randolph Hearst. Walker would go on to develop Red Rocks amphitheater in Denver.

A Car for the Ages

Barber’s vision for Locomobile: to be known as “The Best built Car in America.” That would require funds, which he had, and talent, which Barber would have to recruit. The demographic would have to be wealthy in order to afford the best; this became Barber’s target audience. But first, Locomobile had to transition from its dependence on fragile and problematic steam power.

Locomobile had been producing (Stanleys) since 1899, with the first official Locomobile models in 1902, and the company had been quite successful at selling steamers. However, the steamers were crotchety and prone to breakage and breakdowns. It was time to adopt a more dependable source of power.

Andrew Riker. image courtesy Wikipedia

Barber must have foreseen this, for hired a talented mechanical engineer named Andrew Riker. Riker had started his own electric vehicle company while in his teens, later selling it for $1.2 mil. He believed in gasoline propulsion as the solution for that time, and so Barber sold his control of Stanley patents back to the Stanleys in 1904 and ceased producing steamers.

Locomobile would focus solely on gasoline-powered vehicles from 1905 until its demise in 1929.Barber also relinquished his presidency of the company to his son-in-law, Samuel T. Davis, Jr, who would also be instrumental in marketing the Locomobile. Riker and Davis would form a powerful team that insured Locomobile’s success.

1903 Locomobile, Riker driving. Notice the Renault-style hood. image courtesy Philadelphia Free Library

The Early Cars

In 1904 Locomobile produced two models of gasoline cars alongside their steam car siblings. For 1906, this would change to a range of four gasoline models varying in size, weight, and output as seen in the chart.

1905 Locomobile cars. Catalog images courtesy Horseless Carriage Foundation Library unless otherwise noted

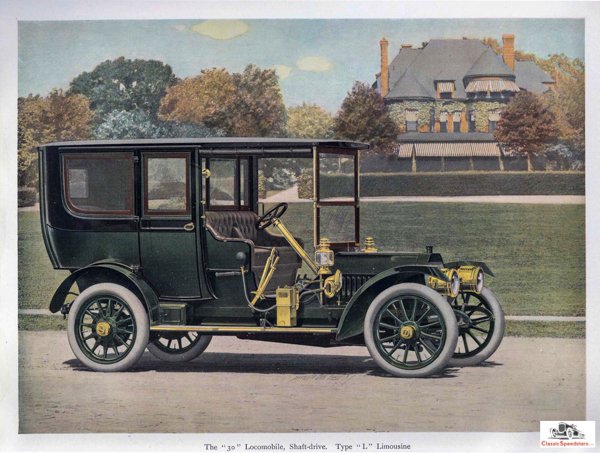

For 1907 through 1911, model numbers would change as would dimensions, with a tendency toward larger wheelbases (up to 125”) and increased output from their tried-and-true four-cylinder powerplant. The types of bodies offered were a touring model, a limousine, and a roadster. What set Locomobiles apart from other conservatively-designed conveyances is that they were built like tanks.

1905-06 Locomobile 15-20 chassis and representative body.

1905-06 Locomobile 30-35 chassis and a representative body. Keep in mind that area coachbuilders were commissioned to build the bodies for the client after they had purchased the chassis.

The takeaway in all of this is that Locomobiles were rugged, were made using the best materials available at the time, and were built to last the ages. The chassis were laid down like a bridge, and every fitting on the bodies spoke of quality. Corners were not cut.

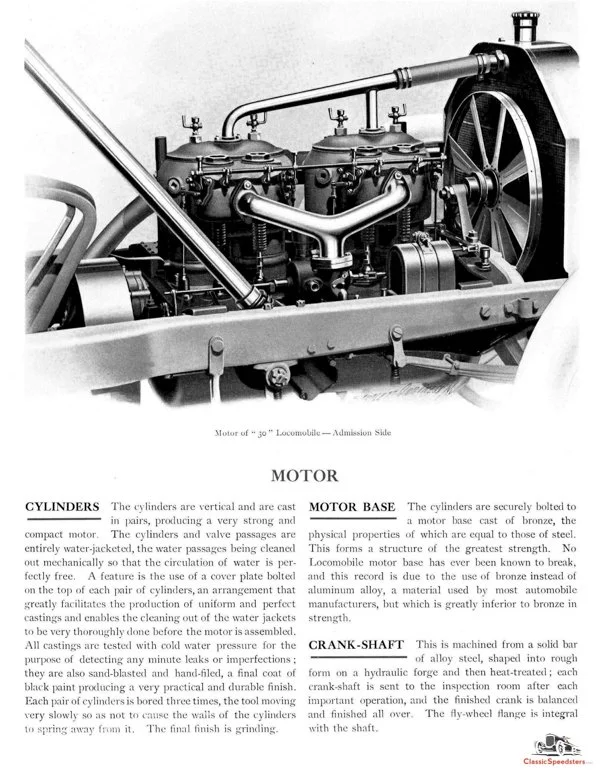

The engine itself consisted of two pairs of cylinders with heads cast en bloc, which eliminated the problem of blown head gaskets. As seen in the diagram, the valves were removed from their “box” for service. Fascinating!

1906 Locomobile engine left side.

Catalog details on how the valves are serviced in a typical en bloc engine with non-removable head, written to prove just how rugged Locomobiles were designed to be!

The Vanderbilt Cup Effect

In the first decade of the 20th century, reliability and endurance were big issues for car buyers. This was not lost on car manufacturers, who gladly prepped their cars for competition and tossed them into the ring to see what they could do.

William K. Vanderbilt Jr competing in a road race. image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

William K. Vanderbilt Jr. had seen the positive effect of motor racing on European car development, and he sensed that this would also improve the American car, which at present wallowed in a state of infancy. His institution of the Vanderbilt Cup Races, the first few of which took place on Long Island, practically insured that Locomobile and other local firms would take up the challenge to race against all comers, since they were located within a few miles of the event. The Europeans came, of course, but by boat. A challenge is a challenge.

Both Riker and Davis were former racing drivers with a bias toward competitive events. Thus, Locomobile was in! Riker designed a special track speedster for 1906 that he knew would give the Europeans something to think about, and two examples were built following the 1905 event in which driver Joe Tracy had achieved second in the Elimination and third in the Main, the first American car in both instances. For the 1906 Vanderbilt speedster, Riker used the model F 110-inch wheelbase chassis (alloy steel) which had a 54-inch tread. 32-inch wheels were used up front, 35-inch in the rear. The four-cylinder F-head engine dimensioned at 7.25” X 6.25”, displaced 1032 cubic inches, and bellowed out 120 horsepower. The monster weighed a compact 2204 libs and cost $20,000.

The famous “Old 16.” Chain drives were required equipment for strength and endurance. This was the most famous American race car of its era. image courtesy The Henry Ford

Tracy handily won the Elimination for the 1906 event, but recurring tire trouble held him to a disappointing 10th for the Cup race. Tracy decided to retire from racing, probably due to injuring a young boy who strayed onto the track.

1905 Joe Tracy in Locomobile racer. image courtesy Library of Congress

There was no 1907 event, so for 1908 the two-year-old track speedster named “Ol’ 16” was dusted off for George Robertson to pilot. Despite tire trouble again, Robertson was allowed to use clincher tires, which sped up tire fixes from 20 minutes to three minutes per. Robertson finished in first with a little over a minute to spare, and Joe Florida’s Locomobile showed up in third, a decisive statement about the quality of Locomobile when up against the best that Europe could offer.

Robertson winning the 1908 Vanderbilt in Ol' 16. This win was significant because it was the first time that an American race car beat the Europeans, who were far better equipped. image courtesy Detroit Public Library

While the Locomobile track speedsters burnished the reputation of ruggedness for their company, it may or may not have inspired program manager Davis to offer a street speedster model that would have traded on the fame of “Ol’ 16.” A runabout model known as a “Fishtail Runabout” would be listed in some of the catalogs for 1906-1907. Unfortunately, no images exist of this model that would corroborate a factory-endorsed street speedster for Locomobile.

In just a few short years, both Mercer and Stutz would be using their track success to promote their cars with street speedsters, a highly successful marketing technique. Instead, Locomobile would focus on its path of conservative, high-priced transportation. How? With detailed descriptions about their cars using high-quality imagery that illustrated just what Locomobile clients would be enjoying.

1909 Locomobile engine discussion, written to affirm the quality behind Locomobile engineering design and execution.

Of course, this quality of car assured the lifestyle that these clients could afford. All they wanted was a car that could get them from Point A to B and back, but safely and in style.

1910 Locomobile Stanhope. The implied message here was, of course, quite evident: if you owned a Locomobile, you lived HERE.

Still, not all of the catalog images featured stately touring models puttering along country byways. Also showing up in the catalogs for 1909-10 were images of manly-man runabouts engaged in various endeavors, with illustrations of the trophies that these juiced Locomobiles were collecting.

1908 Locomobile images as seen in the catalogs. Note that some of the cars were street speedsters with road equipment, proof that sporting Locomobiles were being outfitted for the discerning crowd….

Talk about understated advertising: “The Locomobile was entered in only two contests in 1908; it won both.”

Next episode, we’ll discuss the effect of this type of activity in regards to Locomobile.