Few women from the 20th century are better known by name or more recognized by a photo than Amelia Earhart. At a time when women were still fighting for recognition in a male-dominated society, Earhart seemingly moved about and performed amazing feats with aplomb and relative ease. Clearly Earhart was a symbol for women’s equality and the potential for achievement equal to that of men when given the opportunity. She’d been there, she’d done that. Earhart was and still is a true American hero.

But Amelia was also a speedster lover. How she got her speedster mojo is worth the telling.

Early Life

Amelia and Muriel Earhart on Porch 1904 courtesy Purdue University Archives

Amelia was born in 1897 in Atchison, Kansas at her grandparent’s home. Her mother, Amy Otis Earhart, used a family trust to send Amelia and her sister Muriel to private elementary school. Despite being raised in a proper Victorian setting, Amelia pursued the life of a tomboy, climbing trees at her grandparent’s home, jumping fences and sledding on her belly, much to the consternation of her grandmother Amelia Otis. Young Earhart was a natural explorer and a free spirit, whose formative years in Kansas set the stage for bigger adventures later in life.

The Path Diverges

Amelia’s father, Edwin Stanton Earhart, battled with alcoholism, shifting his residence several times to stay employed and provide for his family. Despite having a family endowment for the education of Amelia and her sister Muriel, the father’s lack of steady employment no doubt affected Earhart family life and led to his eventual divorce from his wife Amy.

Lack of income left its mark on young Amelia. Despite being enrolled in junior college at the Ogontz School in Philadelphia, Amelia never let on that she was impoverished, that she had to repair and alter her own second-hand clothes, and that she skipped meals from lack of funds. Her friends that she made at Ogontz called her “Meelie” and remembered her kind and reserved spirit, a person who was always willing to take a stand on social justice issues.

While visiting her sister at St. Margaret’s University in Toronto in 1917, Amelia came across disfigured and badly wounded young soldiers who had returned to Canada from the Great War to rehabilitate. Their ragged condition so moved Amelia that she dropped out of Ogontz and became a volunteer nurse in Toronto to aid the wounded. She remained there after the war to help those stricken by the pandemic of 1918-19, a flu that killed over 55 million worldwide. These two incidents helped set Earhart on a path of service to those less fortunate, a career that she followed for the next ten years.

Opportunity Knocks

The Earhart family relocated to Los Angeles in 1920, and it was here that Amelia got her first taste of flying. As she wrote in her first book, 20 Hrs. 40 Min., an account of her first transatlantic flight on board The Friendship:

Southern California is a country of out-of-door sports.

I was fond of automobiles, tennis, horseback riding, and

almost anything else that is active and carried on in the

open. It was a short step from such interests to aviation…

1921 (l-r) Anita Snook and Amelia Earhart with Kinner Airster photo courtesy Library of Congress

Earhart’s first flight instructor was Anita “Neta” Snook, who owned and flew a Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck,” a Canadian version of the JN-4 “Jenny.” Earhart would later solo in her newly purchased canary yellow Kinner Airster, becoming the 16th female to earn a pilot’s license. She would also set a world’s altitude record for females in her Airster, attaining 14,000 feet in 1922. This would be the first in a long string of accomplishments during Earhart’s 18-year flight career.

Amelia Earhart’s Flying License 1923 photo courtesy the 99s Museum of Women Pilots

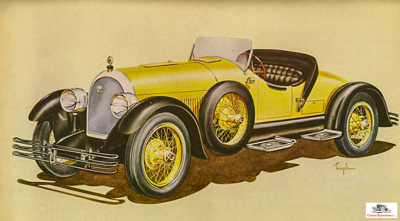

After Amelia’s parents divorce in 1924, the mother and daughters decided to move back east to Boston. Muriel went ahead on a cross-country train to Boston to set up a home. Meanwhile, Amelia had purchased a 1922 Kissel Gold Bug Speedster, the perfect car for adventuring. Which is exactly what she decided to do.

Kissel “Gold Bug” Special Speedster illustration courtesy Antique Automobile magazine

Packing their belongings, mother and daughter drove up the west coast to Washington state, and then on into Canada to visit Banff and Lake Louise. The roads outside of major cities at this time were at best dirt wagon trails for agricultural use, and so road signs were awful as well. At some point Amelia had to trade her childhood stuffed monkey for some needed directions; someone in Canada may still have this toy!

Their trip coursed down through Chicago and on east to Boston. All along the way they were mobbed by curiosity-seekers and well-wishers seeking information about their trip. Any trip was an adventure, and two attractive females in a bright yellow car were an event wherever they stopped!

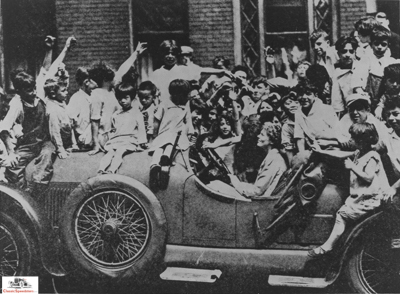

Upon reaching Boston, Earhart found employment as a social worker at Denison House, a settlement house serving Syrian and Chinese immigrant families. Earhart’s tenure at Denison was short, but her personality poured out empathy to its community, and the children she worked with were drawn to her like she was the Pied Piper of nursery tales.

Amelia Earhart with Kissel and settlement house children in Boston at Dennison House, 1925. (Note the orientation of this photo; everyone who has used this photo has printed it backwards up until this point! - ed.) photo courtesy Mary Lovell collection

Earhart had a particular bond with her “Kizzle,” as she called it, its other nickname being “The Yellow Peril.” While at Columbia University, Earhart’s student friend Marian Stabler wrote about Earhart’s affection for her Gold Bug:

She [Amelia] lived poorly and went without everything

but essentials in order to maintain the Kissel car, which

she loved like a pet dog.

However, not everyone was as enamored of the chrome yellow car and Earhart’s driving. Julia Railey, whose husband had recruited Earhart for the transatlantic flight in The Friendship in 1928, wrote about riding to dinner in the Kissel:

At the curb we climbed into the worst looking automobile

I ever saw, bar none. Its rear end was cigar shaped and

its ground color a sick canary. People got out of the way

of it I noticed. [We] scudded through traffic like a car

possessed [and] with something like a flourish

drew up at last at “The Old France” restaurant.

Not everyone can be a speedster fan…

However, Earhart was devoted to her trusty Kissel, and she kept the car well on into 1928, driving around Columbia, New York City, and Boston with friends and family. It was a fun diversion at a time when her prospects were slim and her income meager. More importantly, however, is this take-away: Earhart’s Gold Bug Speedster was her emancipation in a male-centric world. Earhart was in the driver’s seat while in her Kissel.

Forged Alliances, Big Achievements

While in Boston, Earhart had maintained a connection to aircraft, flying a Kinner out of nearby Dennison airport and also representing Kinner as a salesperson. Earhart’s storied career with aircraft had begun in 1921, but really took off in 1928 from her relationship with and (later) marriage to George Palmer Putnam. Known as G.P. in his family publishing company, Putnam would become her publicist and promoter as he recognized Amelia’s star potential and fell in love with her; they would marry in 1929. After the 1928 transatlantic crossing, in which Earhart became the first female flyer to cross the Atlantic (albeit as part of a crew), Earhart pursued flying opportunities while Putnam focused on exposure, arrangements, publicity, and managing news about her. Putnam assisted with publication of Earhart’s first book, 20Hrs. 40 Min., an account of that 1928 flight.

Earhart’s solo flight over the Atlantic in 1932 was the event that put her name in the lights, sparked the possibility of a career in flying, and ended her former years of near poverty and part-time work. As it is true now, small craft flying was an expensive habit in the 1920s and 30s. And despite her growing fame and list of high-society friends such as the Roosevelts, Earhart had to continually seek out endorsements, sponsor products, and pose for ads to help fund her flying exploits.

Fundamentally, Amelia was an adventuress and also a gearhead, so it was natural that she continued her involvement with cars after she sold her beloved Gold Bug. Earhart, along with flyers Frank Hawke and Charles Lindbergh, would promote the air-cooled Franklin Airman line of cars, and Amelia would also own and promote the Essex Terraplane, and also the Cord 810. Earhart loved fast, open, sporty cars, and a speedster or a convertible were the closest things to flying.

Amelia Earhart w 1932 Essex Terraplane. photo courtesy Automotive Collection, Detroit Public Library

Amelia Earhart w 1936 Cord. She loved her convertibles! Photo courtesy Lockheed-Martin

Given her perpetual need for income in order to fly, Earhart was constantly doing something to promote herself and raise money. She lived a choreographed vagabond existence of dinners, appearances, book signings, and public speaking engagements, all to fund her adventures. In 1935 Earhart made 135 appearances at $300 per show; a total audience of 80,000 people would see Earhart speak in person. Her favorite topics were the growth of commercial aviation and its benefit for all, the destructive nature and folly of war, and the good that would come to society from equal rights and opportunities for women.

Despite the controversial nature of these subjects in the 1930s, Earhart was one of the most celebrated and beloved women of her time. People adored her and her speeches, mobbed her wherever she showed up, and sometimes injured her in their efforts just to be close to her. She was featured on several magazine covers, was a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, and traveled frequently as a guest of celebrity friends. Earhart was an accomplished writer and effective communicator, writing regular columns and articles for Cosmopolitan and other magazines, as well as completing two books, her second being The Fun Of It, a further accounting of how she became an aviatrix. Earhart was a Renaissance woman of the 1930s: she lived the life, and she wrote about it as well.

Amelia Earhart and her Lockheed Electra on a 1963 U.S. Airmail postage stamp

Mistakes, Tragedy, and Continuing Mystery

Amelia Earhart World Circumnavigation Flight Map 1937. Image courtesy Purdue University Archives

Her last great flying adventure, an around-the-world record attempt in 1937, was an Ill-timed event that was beset with problems and setbacks. To lighten the flight load and allow for more fuel, Earhart removed the Morse code backup radio and its 250-foot trailing radio antenna. Two of her closest friends, aviatrix Jacqueline Cochran and Earhart’s former business partner, Gene Vidal, observed and commented that Earhart was worn out and not prepared for such a flight. Whether these factors proved mortal, or if it was the blanketing clouds that obscured Howland Island where they were scheduled to land, the fatal flaw remains a mystery.

The facts are that on July 2, 1937, Amelia Earhart’s plane disappeared while fruitlessly searching for Howland Island, a two-mile long postage stamp in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and the U.S. Navy concluded that she had crash-landed at sea. Recent forensic investigators assert that Earhart was pushed northward by unforeseen winds, landed at Milo island, and was picked up by the Japanese, who concluded that she was a spy and subsequently executed her. The complete disappearance of both Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, has never been fully resolved and remains one of the greatest air mysteries of the twentieth century.

Many adventurers risk it all for that momentary rush of accomplishment, and Earhart was no slouch in this regard. She often rolled the dice of fate when she flew and held her life in the balance. On this critical occasion she tragically came up short.

Amelia Earhart 1936 Photo courtesy Purdue University Archives

Amelia Earhart never really sought fame or notoriety. Mostly, she wanted freedom, mastery over her own life, and to have some fun exploring her passions. And for a few brief times in her forty-year life, Amelia did enjoy such moments and recorded them to share with us. Some of these occurred in her cockpit, flying high above the madding crowd, and while earthbound, she spent hours having fun and adventure behind the wheel of her Kissel Speedster. One thing’s for sure: when Amelia was out and about, it was for the fun of it!

******************************

The above is an excerpt from the biography about Amelia Earhart that accompanies the chapter on the Kissel Speedsters that is part of my upcoming book. The book’s title is

Classic Speedsters: The Cars, The Times, and The People Who Drove Them.

More information about this book will be posted as it progresses toward publication. Please stay tuned for further news as it happens!

Thanks go out to fellow authors and research libraries who helped with photographs and facts for this post. Periodically we will highlight a speedster owner and tell his or her story. Coverage of the people who drove speedsters is important, too; their lives and actions have so much to teach us!