Begin the Beguine

Passion often drives a good story to be written. This passion for something pushes the writer to get it down on paper—they must write it.

This passion was true for me and my book, Classic Speedsters. A past memory and the feeling that I felt in recalling it impelled me to pore over material about the topic. Questions kept bouncing around inside my cranium. I had to get some answers.

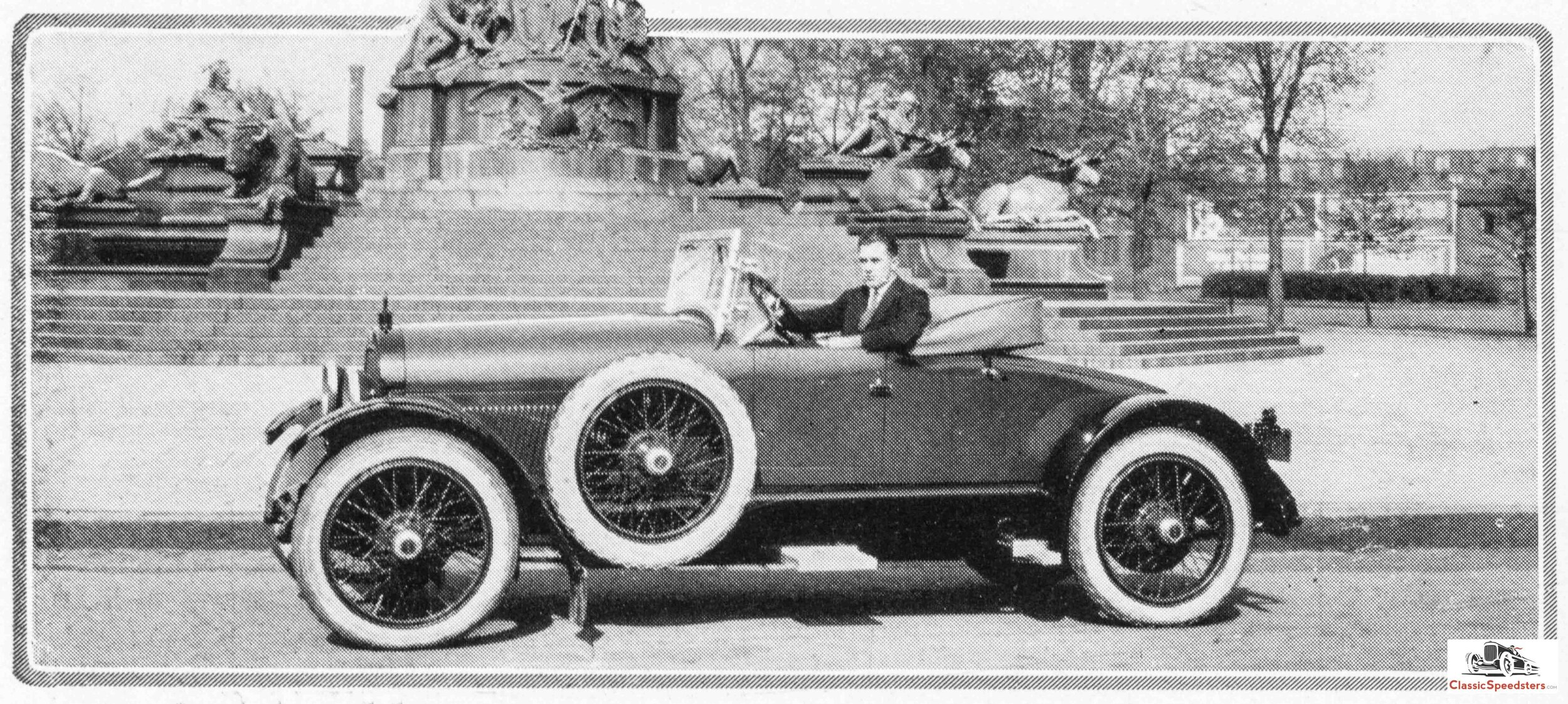

Recognize this image? It’s a 1920 Hudson Super Six ad and I used the image for my site logo.

One discovery led to the next, and disconnected threads started to coalesce and converge around a theme that speedsters were America’s first sports cars. Oddly enough, no one had yet penned a book on the topic; I thought that one should be written to bring it all together, and so on that path I started. That was ten years ago.

Now it’s done and soon to be off to be printed; here is a glimpse at the first three chapters—we’ll cover more later.

Chapter 1: Haynes-Apperson

This ill-fated partnership was a good place to begin the book, as the company was formed in 1893 in Kokomo, Indiana. A bargain was struck between gas line engineer Elwood Haynes and the Apperson brothers, owners of a machine shop, a troubled partnership that modeled the conflicts inherent in 19th and 20th century labor relations.

Riverside Machine Works. This image of the Apperson brothers machine shop was taken in 1895 and appeared in the local paper. Image courtesy Haynes Museum

Conflict drove their split into two autonomous auto companies in 1902; both companies would go their separate ways to successfully produce and market speedsters as part of their line-up.

Neither company would ever acknowledge their former partnership.

1908 Haynes Hiker. Clearly a handsome speedster, this was strictly a street cruiser. Haynes Museum

1905 Apperson Jack Rabbit. Although resembling the Haynes, this speedy devil was ruggedly built to compete and win on board tracks and dirt fairgrounds, which it did with alacrity. Haynes Museum

How they promoted their cars—both companies taking very different tacks— reflects the concerns that consumers had about cars in the early 20th century—performance versus reliability—and how automakers responded to those concerns.

Each chapter features an owner or driver of a speedster from the chapter; in this first chapter it was Olympic champion rower “Jack” B. Kelly of Philadelphia, who won his first gold medal in sculling at the 1920 Summer Olympics.

Jack Kellly’s statue on the Schuylkill River, Kelly Drive, Philadelphia. author image

But there’s more to Jack’s story: along with his wife, Margaret Katherine Majer, a former model who became a collegiate sports coach, Jack provided for his family as a brick contractor. Both raised “Kell” Kelly, a champion sculler in his own right, and both were also the parents of Oscar-winning Grace Kelly (later to become Princess Grace of Monaco). Quite the family!

Jack owned and drove a 1921 Haynes Special Speedster.

Jack Kelly in his 1921 Haynes Special Speedster, as featured in the 1921 Haynes Pioneer magazine. Image courtesy AACA Library

Chapter 2: Knox

The Knox Automobile Company of Springfield, Massachusetts was formed in 1899 by Harry Knox, an innovative technical wizard with an entrepreneurial spirit. Harry attended the Springfield Industrial Institute for his education, worked part time on electrical motors next door at Elektron Manufacturing, and worked at Overman Wheel Company in Chicopee Falls. While off the clock from making safety bicycles, Knox used his time to make his first automobile in 1897.

The Knox Automobile Company was formed in 1899 and made a unique air-cooled engine using cooling rods that projected out from the cylinder wall.

1904 Knox ad. Note the cooling rods protruding from the cylinder barrel, giving it the venerable nickname “old porcupine.” AACA library

Knox Automobile initially made tricycles and later, like many other early automotive companies, moved up to four-wheeled vehicles. Knox Automobile backers would jettison Harry Knox in 1904 and transition the company to having water-cooled engines. Among Knox Automobile’s variety of motorized conveyances rose the promising Knox Sportabout of 1907, and then the mighty Knox Raceabout speedsters of 1908-1912. Few cars could stand up to a Knox Giant and win in any type of contest in this period—just ask race drivers like Barney Oldfield!

1908 Knox Model O Raceabout at speed. author collection

Joan Newton Cuneo, whose bio is featured in this chapter on Knox, was a competitive amateur race driver, and she owned and drove several vehicles that she proudly maintained herself.

Joan Cuneo changing a tire. The car is wisely angled toward the curb in case it rolled off of the jack. Note the details in her Victorian-style hat and dress! image courtesy Jack Hess

Although Joan came from a traditional Victorian background, she was bitten by the speed bug early on and just had to go track racing. And endurance rallying. And hillclimbing… So she purchased a Knox Giant in 1908 in order to accomplish all of this.

Joan Cuneo at Algonquin hillclimb with Louis Disbrow as mechanician. image courtesy Jack Deo collection, Superior Photo

Joan won several significant events in her Knox Giant (which she renamed “Giantess”), enough races to be headlined in newspapers, feted during a major parade in New York City, and interviewed for newspapers and magazines. Cuneo’s accomplishments, however, aroused the ire of social conservatives and laid bare existing cultural prejudices against women trying to become more active and independent in the new century.

All of this mess landed on the conference table of the AAA governing board, which decided that something must be done. And so, in 1909, the AAA issued a permanent ban from participation in racing on Cuneo and on all female automobilists. This ban would be in effect until the AAA gave up its governing power to USAC and other organizations in 1955. Shameful…

Chapter 3: Marmon

How does a world-renowned manufacturer of milling machines end up building automobiles? Answer: when on of the founder’s sons “gets a notion” to build an auto carriage…

Howard C. Marmon graduated from Berkeley as an engineer and started a modest automobile division in 1902, while the parent company, Nordyke Marmon, continued its mill manufacturing operations (which it did until 1924). Howard built his car to be worthy of the Marmon name, and so his cars were sturdy, practical, but also of very high quality. Marmons were famous for several innovations still in use today in the auto industry.

1914 Marmon Model 32 Speedster. AACA Library

Classic Marmon speedsters had been light and sporty, and over several subsequent generations split into two camps: the light and sporty, which were raced, and the large and luxurious, which were cruisers.

1926 Marmon D-74 Speedster, which would become the E-75 for 1927. These were the large Marmons, built on a 136 inch wheelbase chassis, and available in four- and seven-seat versions too. AACA Library

The 1927 Marmon Model L Speedster, a.k.a the “little” Marmon, was constructed on a 116 inch wheelbase but failed to attract Marmonites, dooming it to one year of production. AACA Library

Marmon, like many auto manufactures, was trying to find where the consumers were trending. Speedsters were the tip of this marketing scheme.

Marmon’s most famous speedster was piloted by Ray Harroun, nicknamed the “Flying Bedouin” because of his dark complexion and his ability to find speed in whatever he drove.

1911 Indy 500 poster

Harroun won the first Memorial 500 on Decoration Day at the Indianapolis Speedway in 1911, but there is much more to tell about the man, his inventiveness, and why he faded into obscurity much too soon. Harroun’s bio is part of chapter three.

Ray Harroun colorized postcard commemorating his 1911 Indy 500 win. AACA Library

Next post we’ll look at the next set of chapters..

Until that time, Go drive that speedster!