The Times

World War II ended in 1945, and by 1950, the United States was an exciting place to be for a car guy or gal. The big conflict was over, and the U.S. had not been wrecked by war as had Europe and Japan. Automobile manufacturing had resumed in a big way in the postwar economic boom. Ex-GIs had cash and were buying new and used cars, both domestic and foreign (where available), building homebuilts and hotrods, racing most anything anywhere. And all for the fun of it!

The Companies

The U.S. market for most anything was hot, and this observation was not lost on those in the U.K. and Europe who were looking for markets and opportunities to restart and rebuild their businesses after a devastating war. The U.S. was an economic magnet for businesses that had the contacts and wherewithal to export. One company symbolized the rebirth of European automobile manufacturing, rising from the ashes, literally starting on a dirt floor in a sawmill: Porsche.

American manufacturers had not been idle either, but most of the cars issuing from the Big Three (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) were bulbous, cumbersome boats, leftover concepts from prewar times. The idea that a compact car could be fun and also sell well had not yet dawned on the large conglomerates, but there was one small independent that would venture on this path: Studebaker.

Both of these companies, completely different in size, makeup, and leadership, would make a speedster for their automotive lineups. One car would rise to glory and fame, while the other would fail to gain attention and quickly fall into obscurity. As Charles Dickens had written in A Tale of Two Cities (1859): “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” In this case, it was the best of marketing plans, it was the worst of marketing plans…

Key Players

Dr. Ferdinand and Ferry Porsche, 1938 photo courtesy Porsche AG

Ferry Porsche, son of Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, was responsible for creating the sports car company called Porsche in 1947 as an offshoot of his father’s prewar-established design firm. Despite its humble beginnings in a sawmill in Gmund, Austria, Ferry Porsche’s vision and efforts to build a luxury sports car established a market foothold through hard work, perseverance, and having loyal supporters. One key indicator of greatness was that Porsche won its racing class at the 24 Heures du LeMans in 1951. In its first competitive outing, no less. Talk about gaining instant credentials!

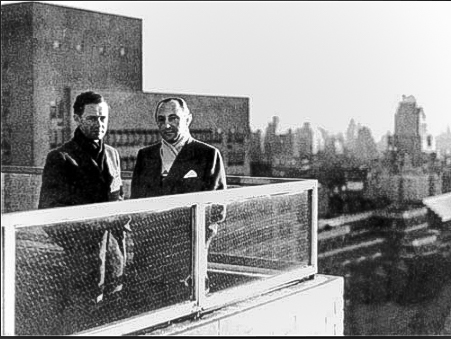

Max Hoffman with Ferry Porsche, 1952, NYC photo courtesy Porsche AG

But it was Max Hoffman, an enterprising car salesman (who had fled Europe to avoid the impending Holocaust that swept most of Nazi-occupied Europe) who convinced Ferry Porsche in 1952 to change Porsche’s market plan for the U.S. This strategic maneuver provided the American market with a fast and dependable sports car and also accelerated the growth of Porsche, an automotive dynasty that thrives to this day.

************************

Studebaker brothers, 1858 Library of Congress

In 1852 three of the Studebaker brothers had formed a carriage-making company. One of them, “Wheelbarrow Johnny,” had left his brothers on a whim, traipsed off to the California gold fields of 1853, and made the Studebaker company’s first fortune, building and selling wheelbarrows to gold miners.

Studebaker’s second strike came when the Civil War began and the U.S. Army badly needed carriages. Settlers moving westward after the conflict had ended also needed transport, and what better way to do it than in a Studebaker?

1880s Study for a Studebaker ad image courtesy Library of Congress

By 1898, and with another conflict at hand, the Spanish-American War (needing carriages again) happened while Studebaker was turning out 75,000 units each year. And the Army once again was buying.

1905 Studebaker Ad. The cars were made by Garford at this time. image courtesy HCFI.org

In 1905 Studebaker was still selling buggies and carriages while investing in successive car companies to establish a toehold in automobile manufacturing. By 1920 it had retired from carriage-making and was soon establishing a reputation as a trusted independent manufacturer of quality cars. After recovering from bad executive decisions that led to receivership during the Great Depression, Studebaker would hire Raymond Loewy in 1936 to help rebuild their brand by guiding their prewar and postwar car designs.

Raymond Loewy in 1953 Studebaker Corp photo courtesy AACA Library

Loewy, the father of industrial design and a multiple award-winning designer with a Midas touch, seized this opportunity to shape car design for years to come. He abhorred the big, bulbous, overweight American cars of the prewar years. He eschewed tailfins and chrome, admired aerodynamic noses and fastback tails, and drew body lines that were simple and curvilinear. Loewy and his company’s designs were controversial because he consciously bucked the Detroit trends, but he knew how to sell his ideas to his clients at Studebaker. And he did.

1947 Studebaker Champion Studebaker Corp photo courtesy AACA Library

The 1947 Studebaker Champion that emerged from Raymond Loewy’s studio was totally different than anything else that Detroit mustered. It was America’s first postwar compact car, anticipating by thirteen years the U.S. market (in 1960) that would give birth to the Ford Falcon, the Plymouth Valiant, and (later) the Chevy II. Controversial, yes, but - nevertheless - a new model of car was thus born, and the American automobile culture was forever made better by it.

It was a foregone conclusion that Loewy would have a speedster up his sleeve too.

The Cars

Porsche cars emerged from a fateful decision that Ferry Porsche made in 1946: “I did not see a sports car that I would like to own, so I decided to make my own.”

1948 Porsche 356/1. Standing (R to L) are Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, Ferry Porsche, and Erwin Komenda photo courtesy Porsche AG

Ferry Porsche and his father’s dedicated design team bivouacked at Gmund for the duration of WWII. Also residing there was his father Ferdinand, who was a design genius of the early 20th century. While at the Gmund sawmill, they developed the Type 356/2 after completing tests on the prototype 356/1, a mid-engine two-seat speedster-like car. The 356/2 was a more practical design that drew upon its Volkswagen roots: a rear-engined, aerodynamically-shaped coupe that would retain essentially the same shape throughout its 18 years of production, from 1948 through1965.

The 356 was first conceived to be a “VW Sports” model, as many parts had been adapted from the Volkswagen Type 1, which was the “Peoples’ Car” that Ferdinand Porsche had engineered in the 1930s for Germany. The Porsche 356 would continuously evolve as it established its market, regularly competed in competitive events, and prospered by astute marketing.

· The company moved its facilities from Gmund, Austria to Stuttgart in Germany after the postwar occupation by Allied troops ended and manufacturing in Germany once again became possible.

· Bodies were initially hand-crafted in aluminum (Gmund) but later switched to steel (Stuttgart).

· Engines were initially two-piece VW modified Type 1 engines (25 hp), but later re-engineered to be three-piece Porsche engines, similar to VW in basic design only, capable of up to 102 hp in street form.

1952 Porsche poster image courtesy Porsche AG

Subtle, functional changes in body style occurred as the 356 progressed through series A, B, and C, but essentially all three series offered a coupe or a cabriolet version, as well as a sporty roadster for the B series and a couple of other variants that will be mentioned later. The Type 616 pushrod engine was offered in two or three levels of tune, depending on the series, and a competition-oriented overhead cam engine, the Type 547, was also offered in various levels of tune (street or track) for the A and B series “Carrera” models. Porsches were meant to be luxury sports cars and were outfitted as such, but influencers both within and outside of the factory would change up some of that in the coming years.

Although sales in Europe were going well for the fledgling company, the market in the U.S. was very price point sensitive, and one could purchase a handsome MG for about half the price or a nice Jaguar for almost even money. Or a Cadillac!

Several sports car makes were handled by Max Hoffman in his Manhattan sales office. He knew the American market, he knew Porsches, and Hoffman knew what would be a good entry price for the car. And so, over a lunch meeting with Ferry Porsche in May of 1952, Hoffman proposed the idea of a simple, stripped version of a Porsche for the American market that would be more competitive in the marketplace, a model that would sell for less than $3000, a low-cost Porsche that would open up the sales floodgates. Hoffman also suggested that, to aid its marketing, they use an iconic name taken from America’s automobile heritage for the new model: Speedster.

***********************************

Studebaker had emerged from WWII with cash in its coffers from lucrative wartime armaments contracts, and the Loewy-designed Champion and Commander models produced strong sales, peaking in 1950 with over 343,000 units. This prompted Studebaker to continue with Loewy Associates to design their next generation. For 1950-on the Big Three favored blunt-nosed, bulbous-fendered, heavily chromed hulks for American buyers, and this flew in the face of Loewy’s European design aesthetic. And, since he was given free reign, Loewy’s design group rolled out a low, sleek, tapered nose-and-tail coupe in 1953, substituting chrome trim and doo-dads with sculpted panel lines, thus making the sleek-looking Champion Regal Starliner striking in its elegant simplicity. It was also lighter than competitor’s cars by 400-plus pounds, making it quick and more fuel efficient.

1953 Studebaker Regal Starliner Hardtop Studebaker Corp photo courtesy AACA Library

Initially selling 170,000 units in the tightening sales market of 1953, Studebaker sales plummeted to 82,000 in 1954, and this seesaw effect re-occurred during the next several sales cycles, fomenting internal dissension and the eventual cancellation of the Loewy Associates design contract.

But not before Loewy rolled out one last design – a Studebaker Speedster!

Next post: the conclusion of this story. In two short weeks. Don’t miss it!