From Ideas to Action

During the childhood years of the U.S. auto industry, hundreds of car companies came and went in an entrepreneurial floodtide, largely unbridled by governmental oversight and regulations. Along with this tide swept in avid, speedster-crazed hobbyists who saw opportunities to buy a fixer-upper and try their hand at making something that would be fast and fun. Again, few regulations held them back. And so, ideas from a thousand tinkerers poured out onto workbenches in garages or under the shade of a backyard tree.

It wasn’t long before results issued forth.

Classic Speedster Designs

The speedster-building craze was already in full bloom when J.W. Hayden of Cambridge, Wisconsin wrote to The Reader’s Clearing House and sent a photo along with his letter. In it he wrote:

“The illustration … is a 1910 Oakland 30, originally a five passenger touring car. It cost $175 for the car. I spent $125 for new parts such as demountable rims, gasoline and oil tanks, Rayfield carburetor, etc. This together with the labor represents the sum total of cost.

“My idea was to imitate the Mercer speedster model and to show how well I succeeded, this picture was taken at Elgin, Ill. last year, and from a distance of one block many of the racing drivers mistook it for a Mercer.

1915 Oakland owner-built speedster. Note the similarity to the Mercer Raceabout!

Hayden continues.

“This model Oakland is easily transformed to a speedster. The steering column is adjustable, that is, it can easily be lowered. The back of the frame is kicked up and by putting on the large gasoline tank, the small oil tank, and the spare tire, you have a neat appearing rear end.”

Hayden concludes:

“…there are a great many of this model in existence and they are to be had at a very reasonable figure. This car will do 50 miles an hour on any country road, which is fast enough outside of the racing game.”

That’s a brisk clip for 1915!

As Hayden had alluded, there were plenty of Oaklands around after Billy Durant took over the company in 1909 upon the death of its second owner. Oakland would become a part of the General Motors family and was good for 3,000-5,000 cars per year, some years better than others. “The Car With a Conscience” became its slogan, whatever that meant.

In 1918 a reader sent in a photo of his conversion of a 1916 Overland 75. Being the smallest Overland for that year, it had a 104” wheelbase and was motivated by a four cylinder rated at a modest 20/25 hp. A short-wheelbase car would do well on a county fair dirt track, and this example had no lighting nor fenders, so it had been purposed for that. Its stubs for exhausts guaranteed a sharp bark and plenty of flames from that minuscule four, but not much else! Still, it looked all the money.

1918 Overland 75 made into a speedster.

The use of a high cowl while keeping the rear deck low and/or exposed was a bridge design that connected the classic era cutdowns to the complete body-skinned sport speedsters.

In June of 1918, a representative of the McCreery-Phelan Company of Memphis had photos published of a Ford Model T speedster constructed in their shop. As he described it,

“The car is underslung about five inches as we procured the necessary drop by using a 60-inch tread Ford axle and having it dropped down … which gives the regular 56-inch tread. The frame was bent in the rear and then spliced to maintain the necessary 100-inch wheelbase.

“The regular Ford engine and transmission are used together with a Bosch magneto and a Heinz starter. We also use the Miller carburetor.

“We may mention in passing that this car was not designed for excessive speed requirements but more for style and general use. However, we have made 60 m.p.h. on the road.”

After some more details, he finishes: “The job is high class and speedy looking, and we recently sold it for $1500.”

There was money to be made for the customizers of that period…

1918 Ford Model T Speedster, well-executed. Note the similarity to the Mercer below.

Many companies, Mercer among them, produced fine interpretations of this style trend. However, it would soon be superseded by an all-enclosed (but topless) body.

1919 Mercer Raceabout. The Raceabout of this series gives more cockpit enclosure and protection for passengers when compared to Mercer’s earliest Raceabouts.

Sport-Bodied Designs

Sporting cars of the late nineteen-teens were moving on to completely enclosed bodies in a variety of styles. Torpedo, turtleback, boattail – there were more, but these three predominated.

Speedsters emulated their track brethren, and higher speeds achieved on track often meant a more streamlined body. The pointed tail and smoothed body line were early attempts to cut wind resistance, often with remarkable looks and results. Model T speedsters lent themselves well to this activity, and the photo below shows one reader’s achievement.

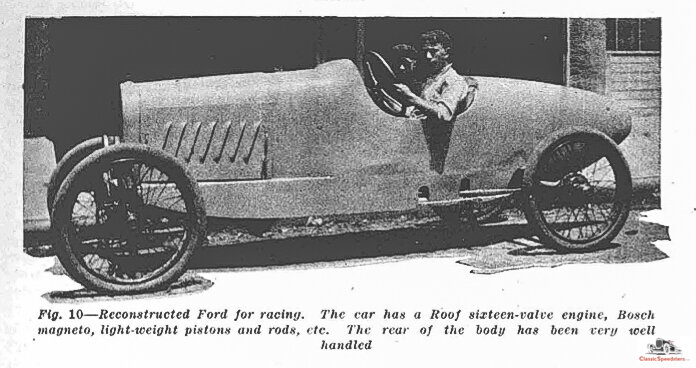

As J. Marshal Yeats of Champlaign, Ill. wrote:

“The accompanying photograph shows my new sixteen-valve Ford racing car built for dirt track work. The car is underslung, using Craig-Hunt parts, giving a six-inch clearance, and has Dayton wire wheels, Roof sixteen valve head, Bosch magneto, 1 ¼-inch Monter carburetor, high-speed camshaft, and Lyonite pistons.”

1918 Ford Model T rebodied for racing. The body is likely a Morton & Brett.

Marshal goes on to say; “It will make a very fast time.” Makes you wonder…

More often than not an erstwhile hobbyist would purchase a pre-made body from one of the many vendors whom we have featured on this site. But in certain cases, the tinkerer had the necessary skills to fabricate his own speedster body.

H.L. Cleveland of the Milner Motor Company in Monroe, Louisiana was one of those fellas. As he related:

“The car was made entirely by me, including the body. The radiator is a Paige, and by narrowing it down 2 inches on each side it has made a nice looking job for a racer.”

1919 Ford Model T Speedster. The fit & finish of this sport-bodied speedster is remarkable. Also noteworthy is that, in a mere 5 years, street speedsters had separated in design from their more functional track counterparts.

Cleveland also shared some engine build secrets:

“The engine has McCadden light-weight pistons 0.031 oversize, Dunn counterbalances on crankshaft, Ford connecting rods lightened 5 ounces each, Bosch duplex ignition, 1 ¼ Master carburetor, Roof sixteen-valve head (Type B), special oiling system, and 3 to 1 gears.”

Cleveland also worked on the suspension:

“The frame was lowered 4 in., this being done by dropping the front axle as shown in the picture, taking a 60-in. axle and dropping it down to 56-in. The rear cross member was cut from the side members and 4-in. goose necks pivoted on, making the rear spring construction the same as the regular chassis, but the frame is 4 in. lower.”

The results? “The car has made a speed of 72 m.p.h. on gravel roads.” For 1919, not half bad!

Some builders were pro shops that built cars for track or street, most likely for clients. In 1918 A.S. Halls of Ortonville, Minnesota sent in some photos of cars that had come out of his shop, and they are grouped together in the photo below.

1918 Speedsters from the shop of A.S. Halls. The Model T (second from top) was a very typical example found on tracks, but outfitted with lights to make it streetable. No doubt this flivver was made to impress the Fast Ford gang!

As Halls relates,

“The cars shown comprise a Lozier Model M, rebuilt for racing purposes,1910 Lozier four passenger, rebuilt into a sporting roadster, and a Ford rebuilt primarily for fast work.

“The latter car (Ford Model T speedster – ed.) took fourth money on the Minneapolis speedway in 1916 on Memorial Day and was driven by me. This car has made a mile is 1 min. 8 sec. on a ½-mile dirt track and one time covered 25 miles in 31 min. 19 sec., during which I changed tires four times.”

Halls reveals some engine secrets:

“The engine is machined on the inside to give equal compression and there is an overhead camshaft, driven by spiral worm gears. The engine uses annular ball bearings throughout, except on the connecting rods.”

For all of that engine modification, one would think that higher track speeds would have been achieved. Some of the early Model T speedsters could, with a little development, pump out upwards of 80 horsepower!

Photos and illustrations from all of these designers, whether they were backyard hobbyists or professional shop owners, reveal a passion for the speedster hobby that has largely gone undiscovered. Only by reading automotive journals from yesteryear can one really appreciate the interest for these cars that was shared by people of this era.

1918 Ford Model T Speedster. No doubt Johnny came marching home again and wanted to drive his speedster to shake off the hurts from a world war.

And there was a lot of interest!

Click on the icon on the left to share this post. Please subscribe using the subscription box on the right to receive an emailed message when the next post comes out.

And comments are always welcome. Leave one below!