Advertising to the public as a means of drawing attention and sales was not a new phenomenon in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century, but the advent of the horseless carriage created a new subject to promote. Each generation of advertising reflects its cultural age, and the ads promoting cars certainly depicted the milieu in which they were created.

One man who recognized an opportunity to tell the story about cars was Claude C. Hopkins, one whom many consider to be the father of “scientific advertising.”

Claude C. Hopkins, early 20th century ad copywriter

Hopkins is more famous for his ad campaigns for Bissell carpet sweepers and Pepsodent toothpaste, products for which he developed promotions by which to sell, coupons with which to test (which techniques worked), and data compilation methods to evaluate his theories.

Hopkins was a restless creative who recognized trends, and on them he built his career. As he related in My Life in Advertising, “One must know what buyers are thinking about and what they are coming to want. One must know the trends to be a leader in trends.”

Hopkins often jumped at opportunities found in developing fields. Automobiles, for instance…

Hopkins on Automobile Advertising

Hopkins first wrote about a steam car that he owned in 1899, a vehicle that provided perpetual challenge as he commuted from Racine to Milwaukee. “When we drove ten miles without a breakdown we boasted of the record… When we ever got through to Milwaukee – about twenty-five miles – we went directly to the factory for repairs, and we rarely returned that day.” Dependability was certainly an issue on his mind at this point, as an early adopter of a new technology.

He soon recognized that he was not the only owner-driver desiring a well-built, reliable vehicle. In the early nineteen-hundreds, “motor cars were not then perfected. Troubles were common, The average buyer thought more of good engineering that of any other factor.” And out of this trend was born an advertising opportunity.

From his work with Chalmers, and then Hudson, and with Overland, Oldsmobile, and R.E.O., Hopkins developed and perfected his method of telling stories in his ads. He named the people who were behind the products, and he had them discuss what the customers of that time wanted to know. Real people producing quality products and telling their stories; there was romance in that kind of testimonial. And it sold!

Just Give Me the Facts

One ad technique used a straightforward telling of the facts. This often ranged from a history of the company’s motorcar, such as Elwood Haynes’ “How I built The First Automobile” (he didn’t), which was published in the company magazine in 1918, and was also distributed as a sales pamphlet to prospective Haynes customers.

Elwood Haynes in his 1920 Haynes Light Six Speedster. photo courtesy Haynes Museum

Haynes was a stalwart self-promoter whose company, based in Kokomo, Indiana, built a series of high-quality speedsters into the 1920s. Their story forms a chapter in my book, Classic Speedsters.

Another example of fact-based advertising was put forth by another maker of speedsters, the Franklin Automobile Company of Syracuse, New York. Their unique approach was to built full-sized air-cooled cars on a lightweight chassis. They touted the benefits of this engineering in their one-page ads entitled “Scientific Lightweight.”

1917 Franklin ad as it appeared in automobile journals

Light weight meant less stress on components (more reliability), longer tread life for tires (up to 20,000 miles driving Franklins when all else begged for 5,000), and better gas mileage (24 mpg compared to others at 8-12). I mean, what’s not to like here?

The Car and the People Who Built It

Colorful art illustration seemed to dominate European automobile ads, often appearing in the form of poster art and popular magazine spreads. In the United States it was the transportation trade journals that dominated, with photos and illustrations in black and white. “The Motor,” “Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal,” and “Horseless Age” were but a few of the many in this field who reported weekly on developing news, racing results, and also carried ads for cars and products.

1906 Cleveland Speedster

The ads for the 1906 Cleveland Runabout Speedster and the 1907 Mora Racytype Six are pretty straightforward: they list the features (“low operating expense”), point out special qualities (“low dropped frame”), and compare themselves to successful archetypes (“Vanderbilt”). The emphasis of these ads asserted reliability and sound engineering. A good buy should speak for itself.

1907 Mora Raceytype Six

Later in this first decade, more pitch was added to the products: some facts, some story, and even a face and a testimonial to help the buying public identify with the person or people behind the product. This technique, pioneered by Claude Hopkins, often had powerful results. To introduce a new automobile called the Hudson, Hopkins introduced Howard Coffin and his 48 engineers as part of the ad promoting Hudson when it began production in 1909. In 1910, Hudson sold 5000 cars, a new one-year record for that period!

The following examples highlight some of the ways that speedsters were pitched using these techniques.

1911 GJG Junior Hooded Dash Roadster and Junior Raceabout

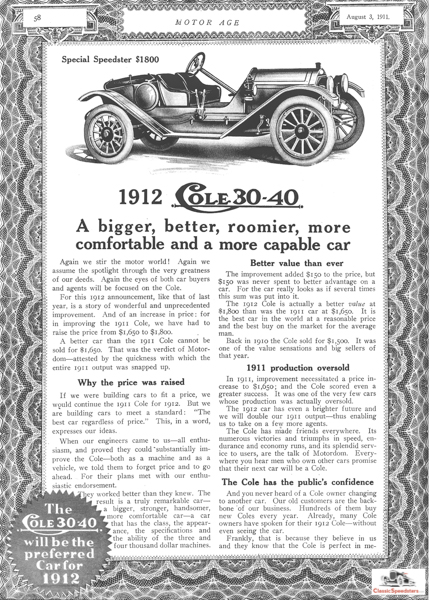

1912 Cole 30-40 Special Speedster

1911 Moon Raceabout, with a personal pitch by owner Joseph W. Moon

Simple Statements, Powerful Imagery

A picture is worth a thousand words, and shown below are early attempts at capturing that which later developed into lifestyle ads, a topic for discussion in another post.

1904 Knox ad. Note the placement of Baby and Mom, gun, and fishing rod. “Go Anywhere” capstones the image.

In this first illustration, Knox Automobile of Springfield, Massachusetts is inviting us to embark on a family weekend, hinting that their car is dependable enough to even get Baby back home safely after a jaunt in the country to the hunting lodge. Knox would build dependable touring cars and very competitive street and track speedsters until economic ups and downs derailed them in 1914. Famous racecar driver Barney Oldfield loved his Knox!

1909 Stoddard-Dayton 9c Runabout

Stoddard-Dayton was a large, well-built car that also enjoyed commercial success into the nineteen-teens. Its 1909 Model 9c Runabout was an elegant speedster built on a 105 inch wheel base and used a Rutenber four cylinder engine puffing out 30 rated horsepower. Its ad was as elegant as the car.

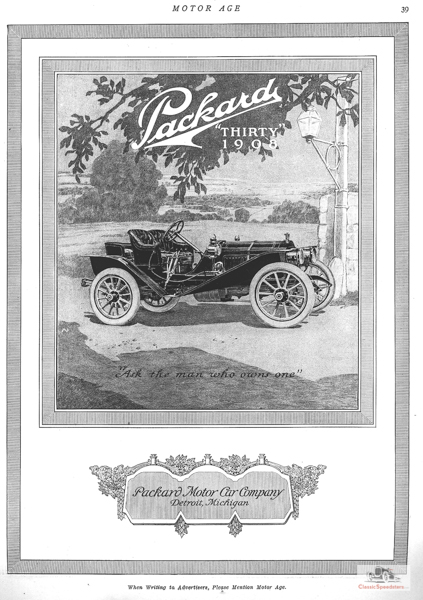

1908 Packard Model 30 Runabout. This was an early cutdown style done the Packard way.

By 1908, the Packard Model 30 Runabout had already been in production for a year, and 1908 represented an upgrade to the concept. Only ten years old, Packard was already using its stalwart reputation as a well-engineered luxury car in its motto, as seen in the ad: “Ask the man who owns one.” And those are all of the words that needed to be written for it!

Next post we’ll look at some other ad trends that emerged in the teens decade of the 20th century and how they involved speedsters.

Several of the cars in this post are covered in my book, Classic Speedsters: The Cars, The Times, And The Characters Who Drove Them. Currently in the latter stages of pre-publishing, more news will follow as we get closer to publication.

Many thanks to the Horseless Carriage Foundation and the Antique Automobile Club of America libraries for use of images found in their collections of period automotive journals.