Right Place, Right Time

William H. “Bill” Sharp was an enterprising fellow during a period when times were a-changing in many arenas in and around his home of Trenton, New Jersey.

Bill Sharp was a photographer, and George Eastman’s Kodak had recently expanded its camera line from a sealed box with celluloid film (1884) to a folding camera and a “Brownie”, the latter being first of many generations of Brownies. These two developments in 1900 would revolutionize and popularize amateur photography in the United States, as well as professional photographic studio business.

Kodak in 1900. images courtesy Wikipedia

1900-era Kodak Brownie camera. image by Håkan Svensson courtesy Wikipedia

Bill Sharp owned a photography studio at the corner of South Clinton Ave. and Beatty St, not far from the Roebling plant, and right next to it he had his Mitchell Automobile dealership, which in 1905 was probably a one-room, one-car showroom/garage.

1907 Mitchell image courtesy Horseless Carriage Foundation Library

Mitchells were built in Racine, Wisconsin, and were known for being solid, conventional automobiles. In fact, during this early period, hundreds of small independents were manufacturing cars with outsourced parts. Like the photography business, car manufacturing was also was a growing industry, and Mitchell was part of it.

Bill Sharp had been interested in speed and competition since the turn of the century. Local newspapers reported that Sharp had raced speed boats on the Delaware River before opening the Mitchell dealership in March of 1905. And in 1907, Sharp had raced a Mitchell in the “Mercer County Championship” event at the September 1907 Inter-State Fair, in which he won first place. No doubt that these activities inspired Sharp to strike out on his own.

Located at the rear of his two buildings, Bill and his brother Fred had an ex-horse stable, shop space in which to tinker away at Bill’s dream – to build a car of Bill’s own design, and a fast one too. The Trenton Evening times was aware of Bill Sharp’s ambition and supported it in a February 1908 post. Bill’s timing and his location would prove to be fortuitous.

Ambition + Good Idea =

While the Sharps were self-funding and busy making Bill’s idea a reality, other developments in Trenton auto-making would soon emerge and indirectly involve the Sharps.

Swiss-born William Walter, owner of the American Chocolate Machinery Co. in New York City, had also wanted to build a car of his own and had actually produced some models by 1901, after which he showed the cars at the New York Auto Salon in 1903, and then formally started his automobile company. Like many a firm, it struggled for recognition in a crowded field.

1907 Walter Automobile catalog image courtesy Tim Kuser collection

Members of the Roebling family of Trenton, famous for wound wire rope and bridge-building, as well as fellow investors from the beer brewing Kuser family, offered their help to fund and produce the Walter in Trenton where there existed ready-made factory space, and so the Walter Automobile Company was relocated and incorporated there in 1906.

1907 Walter Automobile ad. image courtesy Tim Kuser collection

During the same time, young Washington Roebling II had been co-developing a track speedster with designer Etienne Planche, who had been made a superintendent at the Walter factory. “Wash” had ambitions to develop a light fast car and race it. Roebling family backing and Planche’s engineering would enable that dream.

That story gets very complicated at this point, as it leads to the birth of the Mercer and not the Sharp. So we’ll leave this thread to unwind in another post. For now, let’s get back to Bill Sharp and his ambitions…

Promising Starts

By 1908 the Sharp brothers had constructed a conventional, lightweight racing prototype that the Sharps put to immediate competitive use.

1908 Sharp Arrow Speedabout. 1909 prospectus image courtesy Tim Kuser collection

Its first outing consisted of three events that took place in Wildwood, New Jersey on August 3, 1908. At this event the Sharp Arrow logged a mile sprint in 51.5 seconds, and was clocked at 69.2 miles per hour in the process!

Its second occurred at the Labor Day Races at Wildwood, New Jersey during the weekend of Sept 5-7, 1908. During this series of events, the Sharp Arrow achieved a first, two seconds, a third, and a fourth in various race heats.

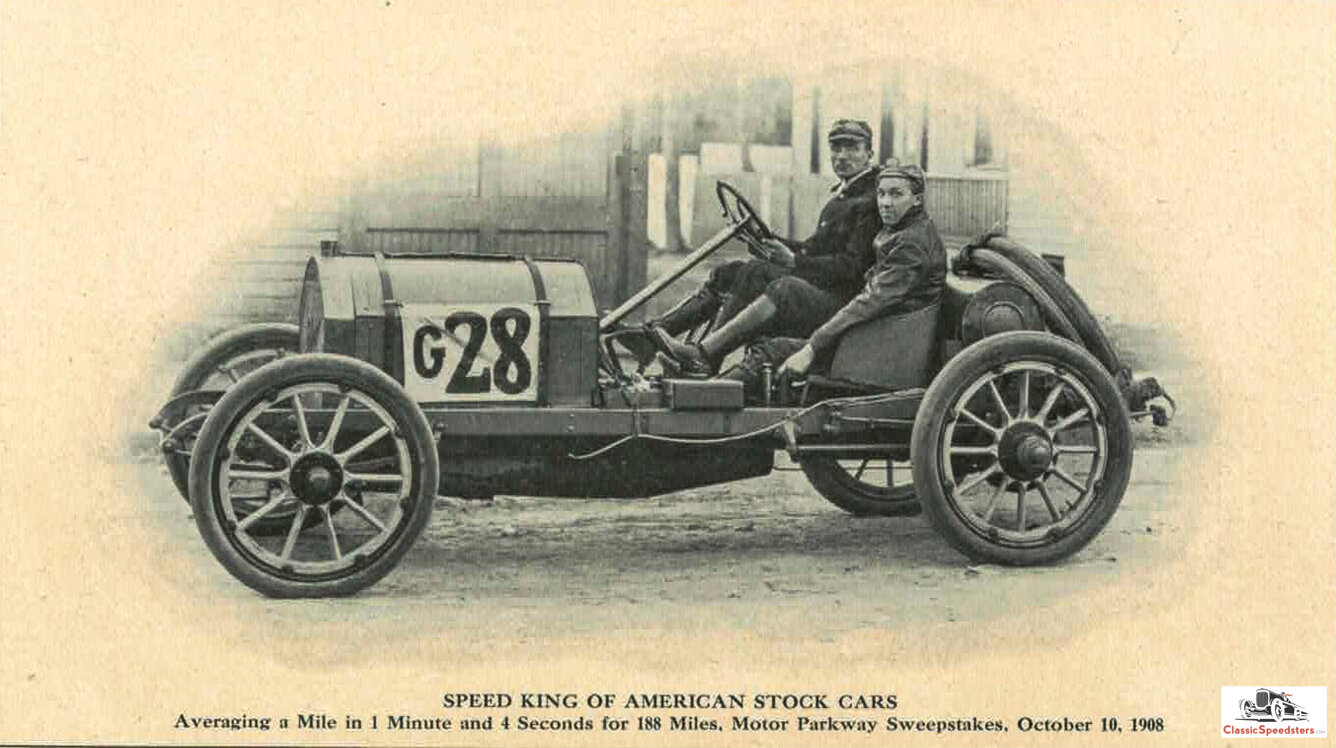

Competing in the October 10th Garden City Sweepstakes, an event held during the Long Island Motor Parkway inaugural races, Bill Sharp piloted and Fred Sharp rode as his mechanic to dominate their class (stock cars costing $2000-$3000) and win it over second-place finisher Billy Bourque, who raced a 1908 Knox Giant. Sharp drove his Speedabout for an average of just under 60 miles per hour and held a 50-minute lead over Bourque. Not a bad result for the Sharp’s third event!

1908 Sharp Arrow at the Garden City Sweepstakes. This photo was also used in ads placed by Sharp Arrow. Note Bill Sharp is driving, while Fred Sharp’s hand is on one of the oil/gas pressurizers, part of his role as mechanician. image courtesy Tim Kuser collection

No doubt this convinced Sharp that he had a winner on his hands, and the Sharp brothers would organize their company in December 1908. Initially capitalized with a modest $10,900, by the time of the 1909 prospectus publication the capital was revised to be (a still modest) $125,000. The Sharp Arrow Automobile Company brochure named the company’s officers, with Bill Sharp listed as President and General Manager.

1909 Sharp Arrow Prospectus, inside title page. Note the capitalization amount. TK collection

In its second season, the Sharp again entered a few events. On May 17, 1909, The Sharp Arrow competed in the Delaware Valley Endurance Run but did not finish. Bill Sharp next competed at a road race in Lowell, Massachusetts on Sept 6, 1909, placing 5th. On the 29th of September, Sharp competed in the Long Island Auto Derby on the Riverhead-Mattituck course, setting a new lap record of 73 miles per hour.

Auto Derby pre-race photo. image courtesy AACA library

Sharp Arrow at the Auto Derby race. image courtesy AACA library

The third season of competitive events commenced with the Sharp Arrow entering the second annual Delaware Valley Endurance Run, achieving a perfect score. On the 4th of July, a Sharp Arrow would place 5th fastest in the time trial event. Another, more fateful event would occur at Savannah in November, which we’ll get to in a moment.

The Sharp Arrow

The 1909 prospectus explained the raison d’etre for the Sharp and illustrated features and specs of the Sharp models. The main points:

• The engine was a Continental water-cooled four cylinder, a 5.0 X 5.0 bore/stroke configuration with jacketed cylinders cast in pairs, displacing 392.7 cubic inches, and rated at 40 horsepower. The transmission featured 3 gears forward and one reverse.

1909 Continental 4 TK collection

1909 Continental 4 Intake-Exhaust Side

• A conventional ladder frame of pressed steel carried half elliptic springs made of Vanadium steel. The runabout and Speedabout bodies were carried on a 106-inch wheelbase frame, while the Toy Tonneau and Touring bodies were fitted to the 116-inch frame. Thirty-six inch wheels supported the whole shebang.

1909 Sharp Arrow Chassis, likely the 106 inch unit used for the Speedabout. TK collection

Promises Made

The prospectus was both a sales catalog and a business plan for the young company. It touted vehicle specifications, competition results, news media comments, and intended market positioning. The Sharp brochure stated that

The pricing of the car was an after consideration. Mr. Sharp started with the idea that a strictly high class car could be built and marketed at a moderate price, that could be depended on the do consistent road work and maintain the sustained high speed of the expensive foreign-built machines.

To sum it up, the “Sharp Idea” was

“… a high grade, medium-priced car, built of the best materials with first-class equipment; guaranteed for hard service, a strong, sure, and speedy roadster.”

Promising Developments

The Panic of 1907 had not been kind to the Walter, an expensive car that had priced itself into a market that dried up with the faltering economy. Despite earning a perfect score in the 1907 Glidden Reliability Trials, the company did not gain any traction in sales, became insolvent, and eventually folded. The Roeblings and Kusers would subsequently form the Mercer Automobile Company out of the ashes of the Walter.

Sharp had planned for 100 vehicles to be built in the first year, with 25 Speedabouts being part of that collection.

Some accounts of the Sharp Arrow Company have it that by 1909 Sharp Arrow was renting space in the former Walter plant and its manufacture was being handled by the John A. Roebling’s Sons Co. Bill Sharp and Washington Roebling II had competed against each other and no doubt were friends; racing communities are often clannish.

According to journal sources, what transpired was that Sharp contracted Roebling Co. to build 10 chassis for him after Sharp’s first-place finish at the 1908 Garden City race had been thrown out. It seems that his car was just a prototype and not yet a manufactured car of at least 10 units, this being one of the race’s rules. Thus, the $1000 prize money and the win had gone to Bourque and the Knox.

However, as Trenton automotive historian Tim Kuser points out, there is no corroboration for space rented at Walter nor Sharp Arrow production by Roebling Co. There may have been a contract, but probably nothing issued from it.

Therefore, what may actually have occurred is that Sharp Arrows were produced one-by-one with local help at the Sharp brothers’ shop on South Clinton and Beatty. Many early auto firms operated using this cottage-industry business model, so it is not unlikely that Sharp Arrow Automobile did the same as they trolled for investors with their prospectus. Newspaper accounts and auto registrations indicate that only 17 non-race cars were ever manufactured by Sharp Arrow. And two known racecars!

Soon enough, cash investment and the potential for further growth came from Mr. W. Burnett Easton, the president of the International Boiler Company. In 1909 he offered to purchase the company and its patents, lock, stock, and barrel, and move everything to Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. Bill and Fred Sharp would be made managerial consultants as part of the deal. This was consummated in December of 1909.

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

Race events that had been held on the Motor Parkway and other road courses had been fraught with participant and spectator accidents, with the mishaps at the October 1, 1910 Vanderbilt Cup race highlighting just how deadly the sport could be.

A look at early twentieth century race movies often showed road race spectators lining the roadways and only stepping aside at the last minute to let the cars through, a promise for trouble. The incidents at the 1910 Vanderbilt Cup caused the cancellation of the ensuing Grand Prize race that had also been scheduled to be run in Long Island; another site needed to be found quickly.

An alternative was hastily arranged by the Automobile Club of America to move the race to Savannah, where the Grand Prize Race would be a closed-course event in Savannah and scheduled for November 12, 1910. This setup would be a lot safer venue than county road races that often produced spectator accidents and deaths due to insufficient crowd control.

The chance to race his car was too tempting for Bill Sharp to pass up, and so off the brothers went to Savannah, with Fred slated to be Bill’s mechanician.

1908 Garden City pre-race photo. Note how clean everything appears! AACA Library collection

1909 Auto Derby Post-Race. Looking a bit grimey, eh? This image would also be used in ads. AACA collection

Something weird happened on the fateful day of practice, November 10. For some reason, Bill Sharp chose another mechanician to ride with him and off they sped onto the course. While racing along the straight at a speed of 88 miles per hour, Sharp lost control of his car and hurtled into the trees and scrub. The car flipped, tossing its passengers and landing on its engine cowl. The mechanician died instantly, and Bill Sharp would linger for two days before perishing from his injuries.

Sharp Arrow accident during practice at Savannah in 1910. This photo was mailed as a postcard on Nov. 10, 1910 to a man in Trenton to relate the sad news. AACA collection

Bill Sharp’s death sealed the fate of the Sharp Arrow Automobile Company, which ceased operations after this tragedy, and Fred would move on with his life. Ironically, W. Burnett Easton, the man who had purchased the company with hopes of moving it to Pennsylvania, had also died in a train accident five days earlier.

As Scottish poet Robert Burns once wrote,

“The best-laid plans of mice and men do oft go astray.”

How true; how very true.

Sharp Bros in their Sharp Arrow. Bill is on left as driver, Fred on right as mechanician. This photo was donated to the AACA Library by Fred’s daughter.

Special thanks go out to Tim Kuser of Trenton, New Jersey, whose keen eye for editing and copious records of historic automotive events in and around Trenton provided much assistance in making this an accurate historical account of the Sharp Arrow Automobile Company.

Be sure to share this post by clicking on a social media button at left.

And if you haven’t yet subscribed, use the red box at right to sign up. We use a two-part opt-in to sign up that protects your security.