Electric Beginnings

It was evident in the 1901 catalog for the National Automobile & Electric Company that they were forging a clear path:

“Our electric vehicles can be understood and handled by a child. They are superior to others in simplicity of construction, ease of handling, durability, absence of noise and other unpleasant features...and elegance of design and finish.”

The 1901 National array of models were not unlike their gasoline competitors—short wheelbase buggies with tiller steering. But they were quiet and they didn’t smoke!

1901 National Automobile models. There was a choice for just about any function! catalog images courtesy HCFI library

National had been started by two members of American Bicycle, L.S. Dow and Philip Goetz. However, the pair must have soon realized the limitations of electric car batteries, for in 1903 they were manufacturing gasoline buggies at their Indianapolis plant, and in 1904 they reorganized as the National Motor Vehicle Company. By 1906 they were focused totally on gas engines.

1901 National factory

Arthur C. Newby, who had helped found the company in 1900, was also an avid cyclist and had worked at Nordyke Marmon before coming to his present position as a director at National. Newby would later become National’s president, create (with partners) the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and guarantee National’s involvement at that track.

1911, Indianapolis Motor Speedway. From left: Henry Ford, Arthur Newby, Frank Wheeler, Carl Fisher, and James Allison. The latter four were the partners that created the Speedway. Image courtesy IMS Library

Newby was a major force behind National in regard to their participation in motor sports.

Performance Bias

1905 Rutenber, a go-to crate motor for builders of the period.

By 1905 National had sorted out their gasoline engine options and chose a Rutenber four-cylinder unit to power their gas models. The Rutenber displaced 283.7 CID with a long-stroke 4.25” X 5.0” and produced 23/30 hp in 1905, increasing to 35/40 in 1906. They would also expand their 1906 line of luxury vehicles with a larger chassis and six-cylinder engine.

1906 National Model E engine

1906 National Model E chassis

In 1905 Newby, a racer at heart, started entering Nationals in competitions, and National did not disappoint. By 1906 each brochure had race results posted within.

1906 National's race results. Early racing events were either match races, sprints, or endurance trials, in this case the lattermost.

National was in the mix in most major automotive events of the early aughts and teens, and it followed from their philosophy as stated in their 1910 brochure for the National 40.

“To our mind the winning of a race proves nothing concerning a factory’s product, unless it is done with a stock car, which differs in no particular of material or workmanship from those regularly on sale. And there can be no other justifiable purpose in racing than to demonstrate the quality of a factory’s product.”

The brochure goes on to state that “no other demonstration of motor-car value will or can survive the same purpose (as racing).”

From 1907 to 1914, National offered a series of street speedsters that easily converted to competition contenders, vehicles that forged the reputation of this company as a serious contender whenever it showed up. Let’s look at some of them.

The 1907 Model L Semi-Racer

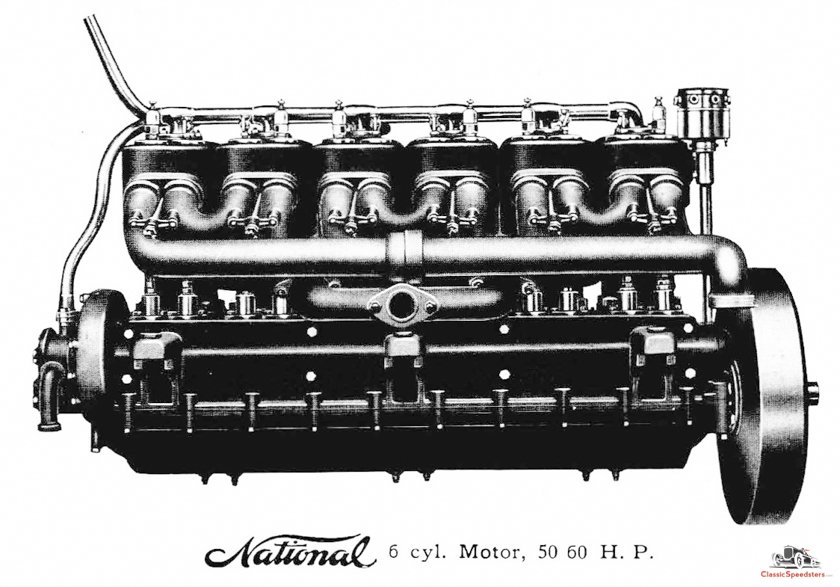

1907 National Model L 6-cylinder T-head. T-heads were more capable of power.

For 1907, National developed a four-cylinder T-head engine of their own, as well as a six-cylinder version with dimensions of 4.875” X 5.0” and displacing a hefty 554 cubic inches. Of course, it needed a strong frame to support such a beast, which produced far more than its 75 A.L.A.M.-rated horsepower.

1907 National Model L chassis. Given the rake of the steering column, this chassis was a touring unit.

The Model L chassis had a 127-inch wheelbase.

The Model L itself had a long hood to accommodate both the size of the engine as well as the design imperatives of the time; a long hood meant that a big and powerful engine lurked beneath. This image was a big deal in early 20th century car design!

1907 National Model L Semi-Racer side view. Note the long hood!

1908: A Year of Choices

For 1908, the six-cylinder engine was offered in two choices. A 589 CID 5” X 5” engine was made for the touring bodies and referred to as the “Model T Motor,” but of course had no relation to Henry Ford’s dinky little unit of the same vintage.

1908 National Model R engine

Then there was the “Model R Motor,” a 4.5” X 4.75” engine displacing 453 CID. Still, a monster motor for a speedster on a 106-inch wheelbase. The Model R Roadster was not for the faint of heart!

1908 National Roadster models

For those sporting types that wanted a little less oomph but the same panache, there were two choices of four-cylinder “sport roadster” available using a 102” chassis, the Model K with a 373 CID engine, and the Model N with a 393 CID powerplant. Still, both had lots of yowsa in them!

These models would change model names and the engines were upgraded for 1910, but they largely continued as-is. National’s focus on improving their product through competition certainly racked up their race records, and sales increased incrementally, but this was never a major auto firm with thousands of its cars roaming the U.S. and elsewhere. Rather, National continued on as a small independent with sales that swelled to almost 2000 units sold by 1915, but never more than that, and most of the time closer to 1000.

1910: The Models 40 and 9-60

The year 1910 proved to be a breakout for National as it moved on from its longhood semi-racer models, and its cars would soon make history in some of the biggest racing events of the early twentieth century. One up-and-comer was National’s Model 9-60.

1910 National Model 9-60. Savannah was a big race on the annual road racing schedule.

The new decade brought with it a sophistication in racing car technology. The concept of taking a street speedster, stripped of road-going equipage, to the track for a win was still eminent, and National was in the mix with the Model 9-60 as well as the four-cylinder Model 40 examples. As the marketers wrote about National’s experiences at the new Indianapolis track,

“Kindly note that the first two cars of the new National “Forty” that came though the factory won their laurels at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway races in competition with specially built race cars, and demonstrated their worth right handsomely.”

So, how did they do?

A three-day event, August 19-21, scheduled a variety of sprints and longer events at the recently completed track, whose racing surface would prove to be problematic and, in some cases, deadly. However, the National team was able to sidestep the controversy over the “taroid” mixture (tar and gravel) and soldier on through.

On August 19, Aitken placed third in his National 9-60 in the ten-mile sprint. For the 250-mile race, Merz and Kincaid brought their National 40 stripped stock cars home in third and fourth.

On Friday, August 20, Merz in his National 40 captured the first ten-mile sprint, while Aitken in his National 9-60 won the next sprint and collected a second place in the third event. For the last race of the day, a five-mile handicap, Aitken (9-60) barely nosed out his teammate Merz in the National 40, both achieving a 4:25 race time, equaling the existing world record on standing-start sprints. These cars were torque monsters!

For Saturday, August 21, a variety of events were held, and the images below summarize National’s day in the sun.

1910 Aitken at Indy

1910 National 40, winning!

The street version of the National 40 was a sport roadster, its chief distinguishing mark being cursory doors on an otherwise speedster body This was a smart precaution at a time when seat belts were non-existent!

1911 National Model 40 Speedway Roadster

1911: The National 40

The company focused on its National 40 model for competitions in 1911. At Speedway meets such as Atlanta and Indy, National won 20, placed second in 27, and showed up third 23 times. It won the hillclimb at Algonquin Hill in Chicago and performed very well in the three road races for the year at Elgin, Vanderbilt, and Fairmont Park. Including beach races, National racked up 162 podium finishes for the season!

1911 National wins ad

1912: Winning the Laurels

In 1912, National issued two versions of the Speedway Roadster, the Standard, which retained its elegant speedster styling, and the Series V which was more plushed out in roadster style.

1912 National 40 Speedway Roadster in “Standard” trim.

1912 National 40 Speedway Roadster Series V, a deluxe version with a higher door, better seat materials, and more enclosed cockpit.

The engine for the Speedway roadsters, whose 120” wheelbase rolled on extra-wide 36” X 4.5” tires, was a 5” X 5” four-cylinder, a T-head of 393 CID capacity. Like other sport models from National, this car was not meant for dandies!

1912 National 40 chassis & engine

In the competition world, National 40s had crested, and the company decided to enter but one race. A National 40, piloted by Joe Dawson, won the 1912 Indianapolis Sweepstakes on the bricks, a fitting testament for the Model 40. For 1912, National sold 1410 of all models.

1912 Indy 500 winner. National won the laurels, and this beautiful illustration, penned by David Story, is featured on Mark Dill’s FirstSuperSpeedway.com site. Thanks to both for permission to use this image!

1913: What’s Next?

In 1913 National formally decided to leave racing. The sport itself was still in its infancy, and perhaps the prevalence of injury and death in this arena soured the board of directors, who steered the company toward producing fine cars and increasing market share in the luxury market. Nationals had cast aluminum bodies, rugged frames, ironclad suspension and drivetrain, and torquey engines. Why not bask in the sunlight and focus on income?

1914 National 40 suspension pieces; rugged stuff!

Along with the touring models, a Speedway Roadster that was more enclosed was produced, and speedster fans enjoyed the re-entry of the Semi-Racer. These would continue into 1914.

1913 National Semi-Racer ad. Contrary to the message content, that woman is not thinking about the comfort of her cabin. No way! She’s gazing out the window at that 1913 Semi-Racer and wondering about the manly-man who drives it!

1914: Swan Song for the Semi-Racer

For some reason the company felt compelled to explain its decision to leave racing, as it summarized in its 1914 brochure, which was released in 1913:

“Race victories with us do not stop at the end of a race—they live forever in the character of your car and the way it is built. Racing is not an end, but a means; a school for our engineers; a test for our materials; and absolute proof of our quality; a positive guarantee of our reliability as well as stamina.”

This would be the last year for the semi-racer, and a look at its Generation-1 speedster profile shows that, given the increasing concerns about safety, it was appropriate to move on to more enclosed bodies, which National would soon do.

1914 National 40 Semi-Racer: is this your poison?

1914 National 40 Speedway Roadster: or would you rather drive this?

The Series V-3, as these two models were known, used a long-stroke configuration for even more torque than it had formerly employed. A 4.5” X 6.0” configuration produced a slightly smaller 382 CID engine, probably even more powerful than its predecessor.

1914 National 40 Series V engine intake side

1914 National 40 Series V engine exhaust side

The two sporting models retained the 120” wheelbase and enjoyed further technological improvements, such as an electric starter and double-rear brakes.

1914 National 40 chassis

Sales literature for 1914 touted the National as the “World’s Champion Car,” as it had dominated Indy in 1912. However, this sales pitch would disappear, as well as the Semi-Racer and Speedway Roadster, in 1915.

1918: A New Beginning, or Beginning of the End?

In 1914, sales for National peaked at almost 2000 units, but from that point sales dwindled. In 1915, National was one of the first to offer a 12-cylinder engine for its “highway” series. The 370 CID engine had a 2.875” bore and a 4.75” stoke, making it very torquey and thus easy to drive. But, was a twelve really needed for more torque, or was this just a way to keep up with what other brands such as Packard were doing?

As part of its marketing outreach, the 1918 catalog featured women riding in, driving, and even maintaining the Highway Twelve. Fancy that!

1918 National Highway Cars “Airplane Type Motor” brochure. Wartime aircraft were using 12-cylinder engines for the “big birds,” and National capitalized on the “big” by offering a 12-cylinder. This engine was a real had scratcher, but what is more clear in this series of ads is that the target market is women. The hidden message here was that “even the weaker sex can own and drive a National.” Those were the days….

However, this maneuver didn’t seem to work, as sales continued to drop.

Perhaps in a separate effort to bolster sales, National offered a turtleback sports model for 1918-19 on a 128” wheelbase. Known as the Speedster, it was right in synch with what other companies, such as Kissel and Marmon, had been barnstorming with some success across the country.

1918 National Highway Cars Speedster. Its resemblance to the Kissel Gold Bug and the Marmon 34 is quite remarkable. However, the National Speedster had a “twelve” in it!

Still, it was not enough to help the company out of its slump. The post-WWI depression of 1920-21 would hit all companies hard, but it crippled National, which continued to produce cars through 1924, but they only numbered in the hundreds, with 183 produced in its final year.

In comparison, Ford Motor Company built and sold 1,922,048 that very same season…

However, you can’t take away National’s 1912 Indy victory!

*************************** *********** ****************************

The Speedster blog is approaching 100 journal entries, which represents four years of spreading the love about speedsters and their influence on cars and culture. What a journey it’s been!

News Flash!

My book, Classic Speedsters, is now available on Amazon.com, but you can still grab yourself a copy at ClassicSpeedsters.com. Go get yourself a copy today!

**********

I’ll soon be switching gears to focus on other writing projects that are knocking around in my head, and I’ll be parking this blog for a bit while I do that. only so much time in our days, eh?

If you’d like to find out more about my writing, or just keep up with what’s going on, let me know — email me at

SteeringWheelPress@gmail.com

I’ll put you on my newsletter list so you can receive the news as it happens. And boy, exciting developments are just about in the hopper!

Until then, go drive that speedster!