The years 1911-1920 saw a monumental growth and expansion of automotive brands, models, and technology. The SAE, as noted in a previous post, met in 1916 regarding model nomenclature and definitions, codifying them by 1922. However, as common as the speedster was among casual onlookers and enthusiasts alike, the SAE failed to define or describe what it was. Fancy that!

1912 Cole Special Speedster ad. Illustration courtesy Horseless Carriage Foundation

The speedster in this era was a copy of what many folks could see in competitive events, but by 1913 most examples racing on a track were far more sophisticated and rugged than their streetside cousins. Nevertheless, the progression of this decade witnessed a transition from open-deck cutdown speedsters to more enclosed bodies, some even with doors, in an effort to provide the same thrills but with more protection.

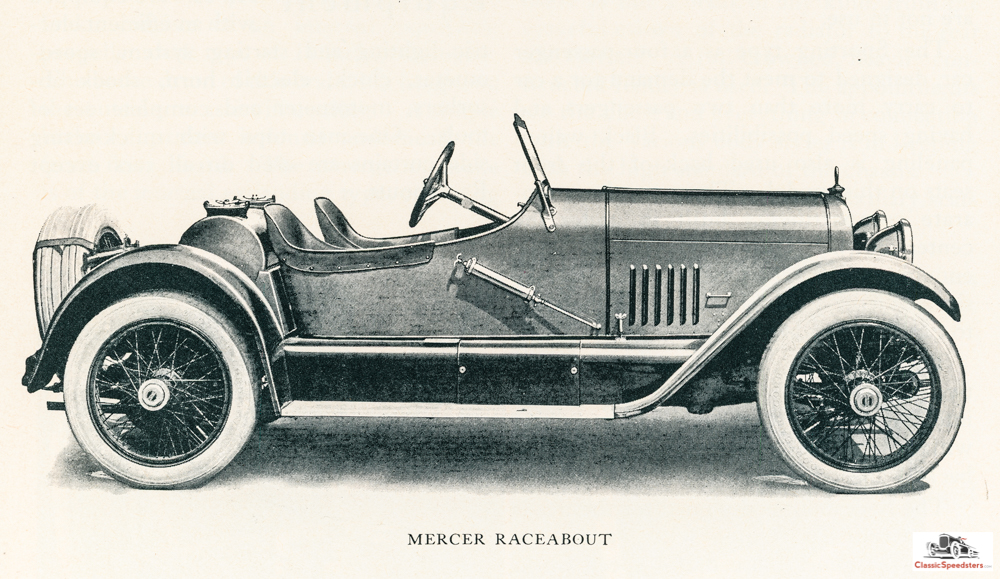

1911 Mercer Raceabout from catalog. Image courtesy AACA Library

1919 Mercer Raceabout. Note that the body is now more enclosed as in the earlier Runabout body styles. However, no doors (yet).

Scores of companies offered a speedster in their lineup, and the range of names was only limited by a designer’s imagination. This creative naming would reach a peak in the 1920s, which we’ll cover in a later post, but below are but a few of the names one could wonder at in the nineteen-teens:

• 1912 F.A.L. Speed Car

• 1912 Locomobile Gunboat Speedster

• 1912 Hudson Mile A Minute Speedster

• 1913 Kline Car Meteor Speedster

• 1913 Marion Bobcat

• 1914 Stutz Bearcat

• 1914 Detroiter Series A Kangaroo Speedster

• 1914 Kearns Lulu Speedster

Now, don’t these names beat all?

Several companies that had a robust beginning and a bright future were felled by the roiling economy of the aught and teen years, poor business decisions, or just their founders’ egos getting in the way of sound judgment:

• E.M.F. (reported on in a previous post) consisted of three talented and successful automotive giants who just could not stay together long enough to grow their promising empire that they formed in 1909. Their grand conceit would fall part by 1912, but not before producing one or two fine speedsters!

1912 Studebaker-Flanders Speedster. Image courtesy AACA Library

• Knox had had a solid beginning in 1900 and marketed a popular series of speedsters starting in 1908, but by 1914 its car division was folded up, in part by an economic downturn and overdue banking obligations.

1911 Knox Model S Raceabout. Note the “double rumble seats” - an exciting ride in its time! catalog image personal collection

• Stutz had an auspicious beginning, rolling out a prototype speedster in 1911 in time to make a decent run at the inaugural Indianapolis Sweepstakes on Decoration Day. Stutz claimed 11th overall after the dust settled and the race organizers had spent three days determining the winner! Stutz’s motto immediately became “The Car That Made Good In A Day.” Unfortunately, Stutz “went public” in 1915 to raise needed capital, and into the firm slipped an investment wolf who bought up the common shares on margin and then wrested control of Stutz from its founder. Ousted from his own company in 1919 but not yet outdone, Harry Stutz moved across town and began again with a new company named H.C.S. (not to be confused with a model series of cars from 1915 that had also used his initials).

1914 Stutz Bearcat. catalog Image

1914 Stutz H.C.S. Speedster, also known as the “Baby Bearcat.” article image courtesy HCFI.org

The H.C.S. Speedster was also referred to as a “Baby Bearcat,” but this model would not be continued in the H.C.S. Motor Car Company. Stutz would pull itself together and motor on into the thirties using its famous speedster line, the Bearcat, to showcase the brand. However, H.C. S. was not as successful after commencing in 1920, producing not more than several hundred cars a year and folding by 1925.

Typical Ads of the Era

Ads that appeared in The Automobile, Motor Age, and the Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal, as well as other journals and even popular culture magazines, continued to evolve the story line found in their content. A snappy hook, a race result, an interesting anecdote or testimonial: these were typical in the teen-year ads.

1911 Cino Raceabout as it appeared in Motor Age. Ad courtesy HCFI.org

In 1914 Barney Oldfield won the Desert Classic using Houk Detachable wire wheels. ad courtesy HCFI.org

1919 Marmon ad featuring its Liberty Engine Award. Marmon was famous for its engineering accuracy and machine fabrication tolerances. ad courtesy HCFI.org

Auto Show News

Annual automobile shows were branching out from New York and Chicago to smaller cities and more widespread regions as roads improved and cars began to take over. Remember that horses and carriages were still common fare and not be fully superseded until 1918. The auto journals would provide extensive coverage of new body types and styles as seen at the shows. Often different makes would be grouped in these articles using common themes for comparisons between the makes.

Runabouts featured at the 1912 Chicago Auto Show. Note the Hudson Speedster at the bottom, significant in its lack of doors. Yowsa! article image courtesy HCFI.org

Lifestyle Ads

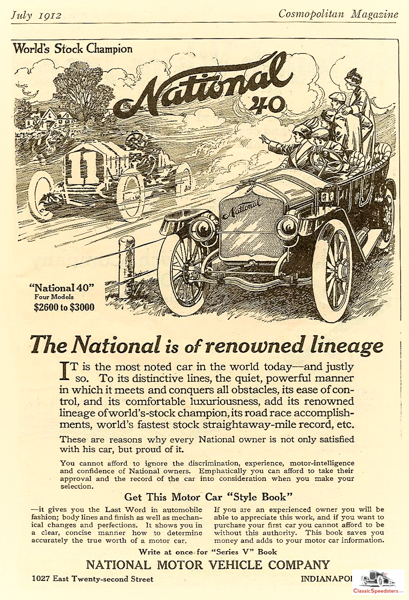

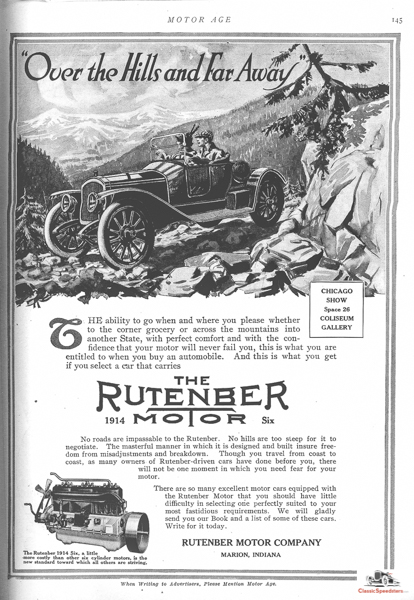

This type of ad did not really take off in the nineteen-teens; up to this point the car’s durability and efficiency, as well as the reputation of the manufacturer were the salient points of most ads. Marketers in automobile-land had not yet fully connected lifestyle and income to automobiles and consumers. However, there were a few inklings of this trend during the nineteen-teens worth noting, as seen below. Racing and adventure continued to be associated with speedster models, but sedans and tourers needed to be sold. Note the linkage in the National ad!

1912 National, on track and street! ad courtesy HCFI.org

1912 Rutenber engine ad. Rutenbers were used in several cars whose companies produced an “assembled car” and required a turn-key crate motor. In this case we have a speedster! ad courtesy HCFI.org

The lifestyle ad would blossom in the 1920s with multi-color layouts of wishful thinking scenarios. This we’ll look at in the next decade of this series. Watch for it!